My eMHR Personal Health Records Subscription Plans

|

Bronze Package

Free

- Medical Records Mgmt.

- File Management

- Patient's Report(s)

- Transmit Records via Email

- Medical Resources

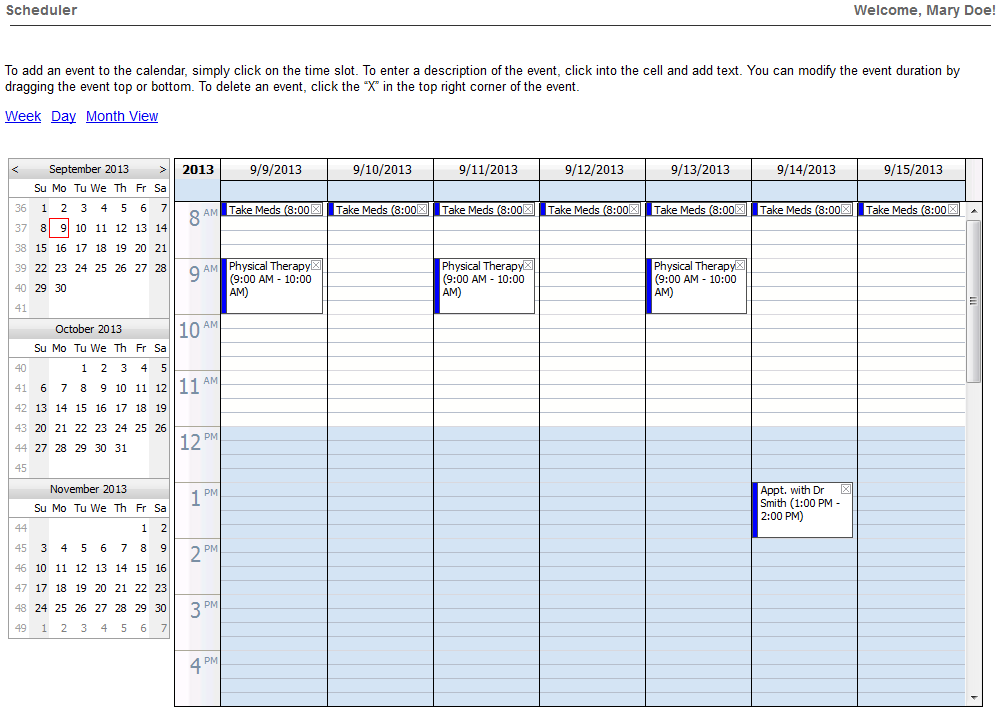

- My Scheduler

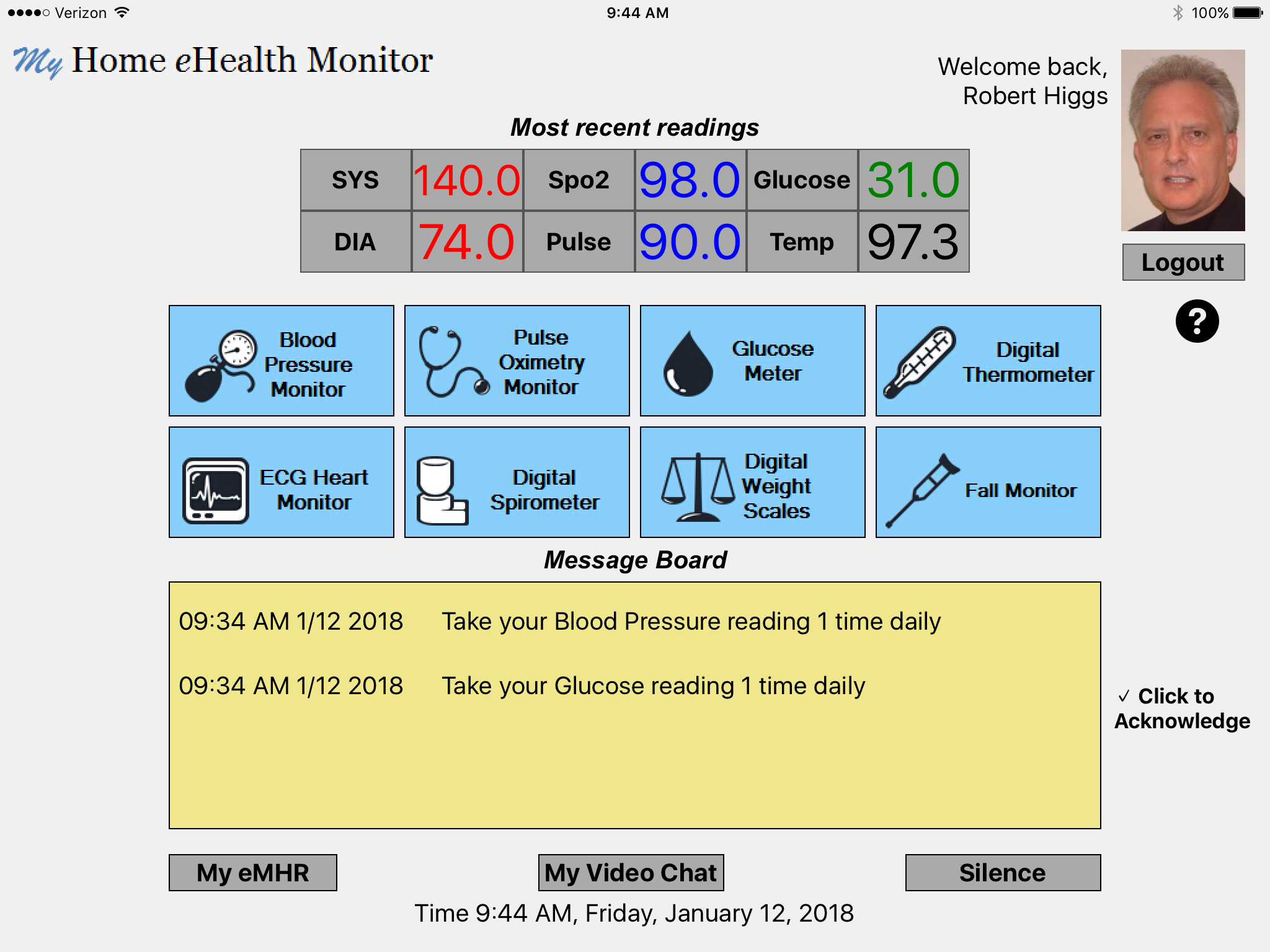

- My Home eHealth Dashboard

- ISeeYouNow

- My Health Mobile App

- 25 MB Storage Allowance

- All apps in iOS and Android

|

Silver Package

$49.00

User/Annual

- Medical Records Mgmt.

- File Management

- Patient's Report(s)

- Transmit Records via Email

- Medical Resources

- DICOM Viewer

- My Scheduler

- My Home eHealth Dashboard

- ISeeYouNow

- My Health Mobile App

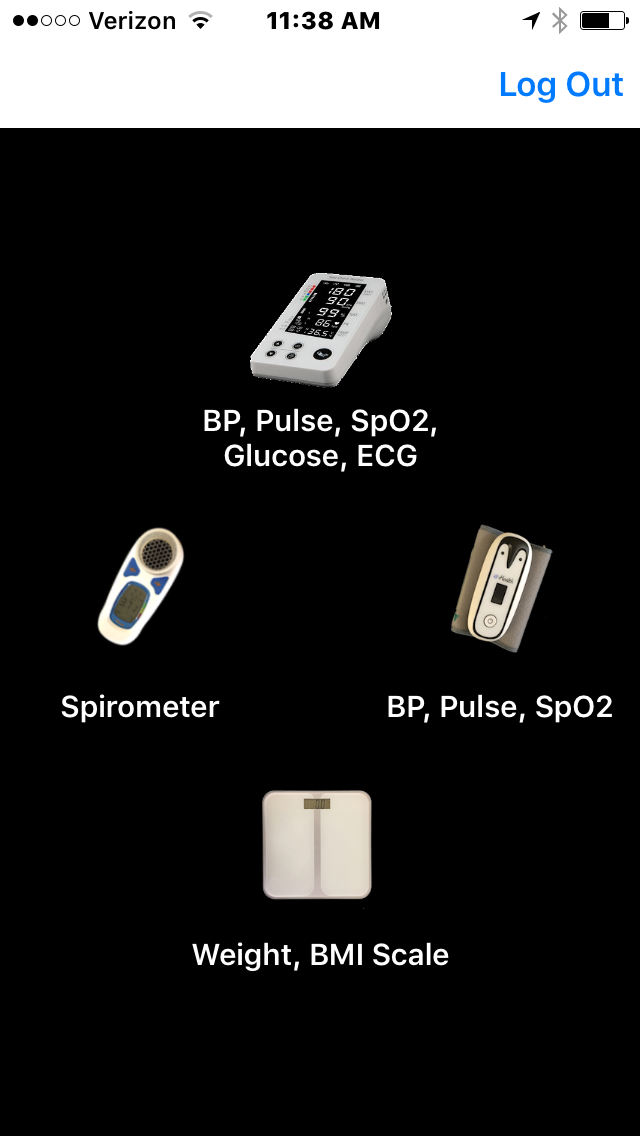

- My Health Vitals Mobile App

- My RESP Check Mobile App

- 100 MB Storage Allowance

- My eTeleHealth Portal

- All Apps in iOS and Android

|

Gold Package

$96.00

User/Annual

- Medical Records Mgmt.

- File Management

- Patient's Report(s)

- Transmit Records via Email

- Medical Resources

- DICOM Viewer

- My Scheduler

- My Home eHealth Dashboard

- ISeeYouNow

- My Health Mobile App

- My Health Vitals Mobile App

- My RESP Check Mobile App

- My Home eHealth App

- Unlimited Storage Allowance

- My eTeleHealth Portal

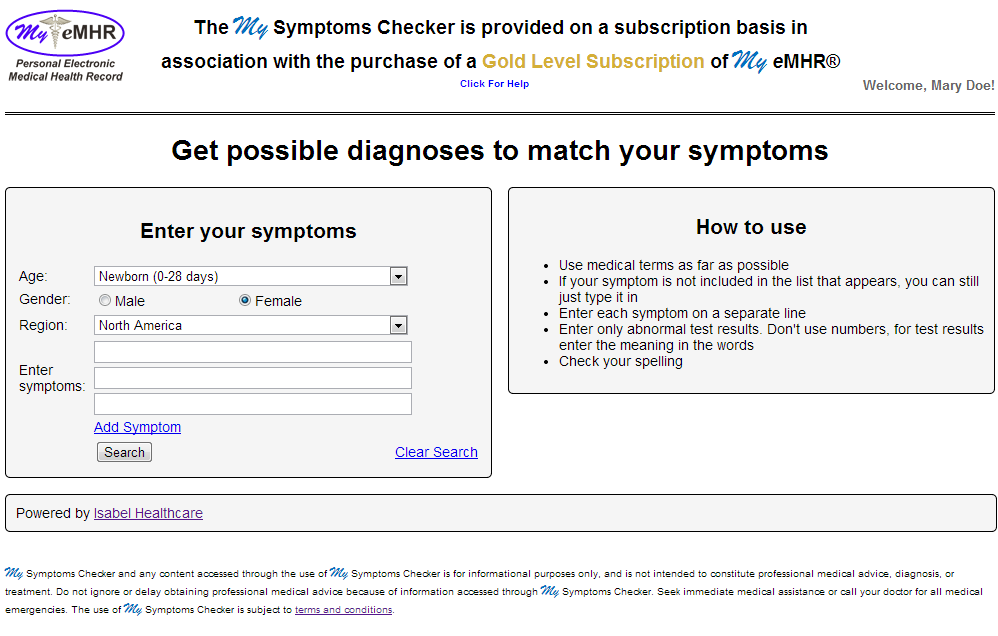

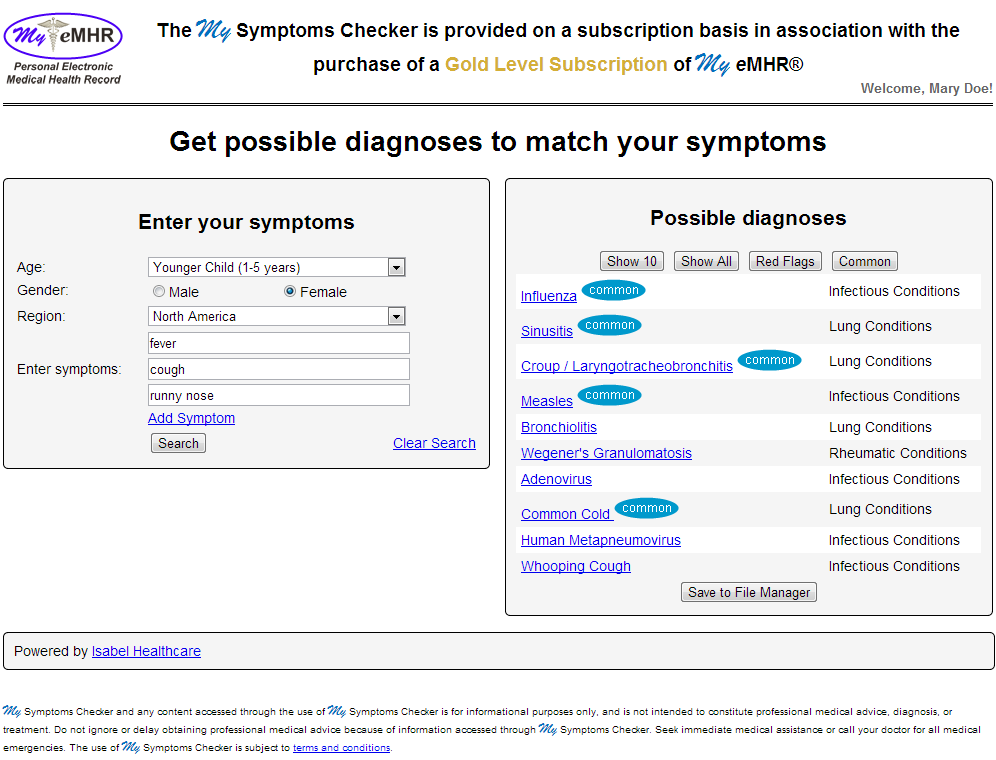

- My Symptoms Checker

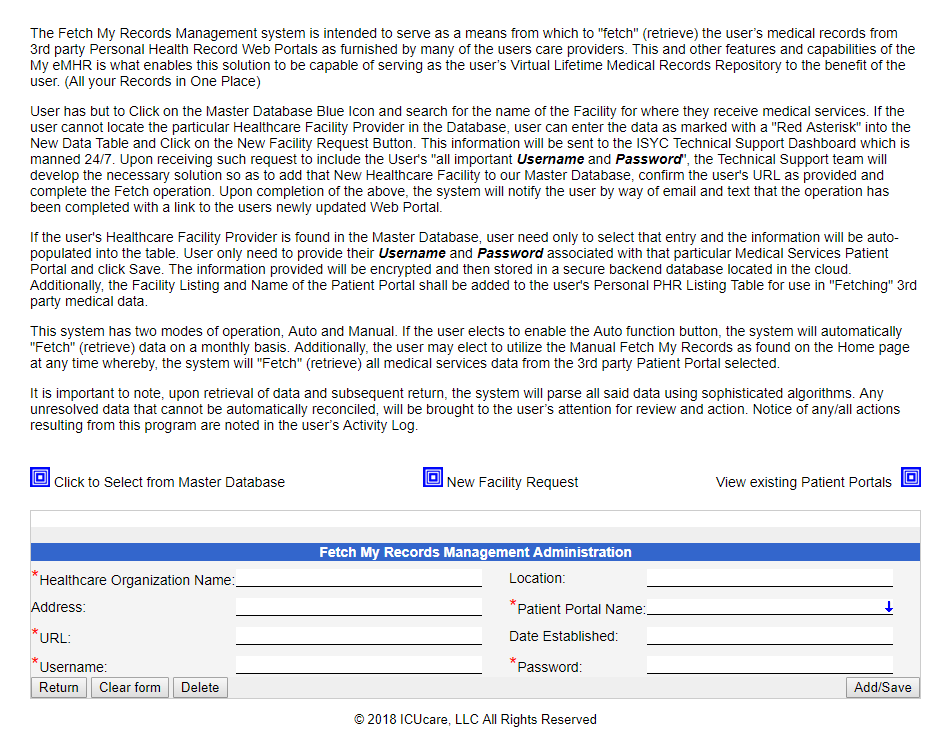

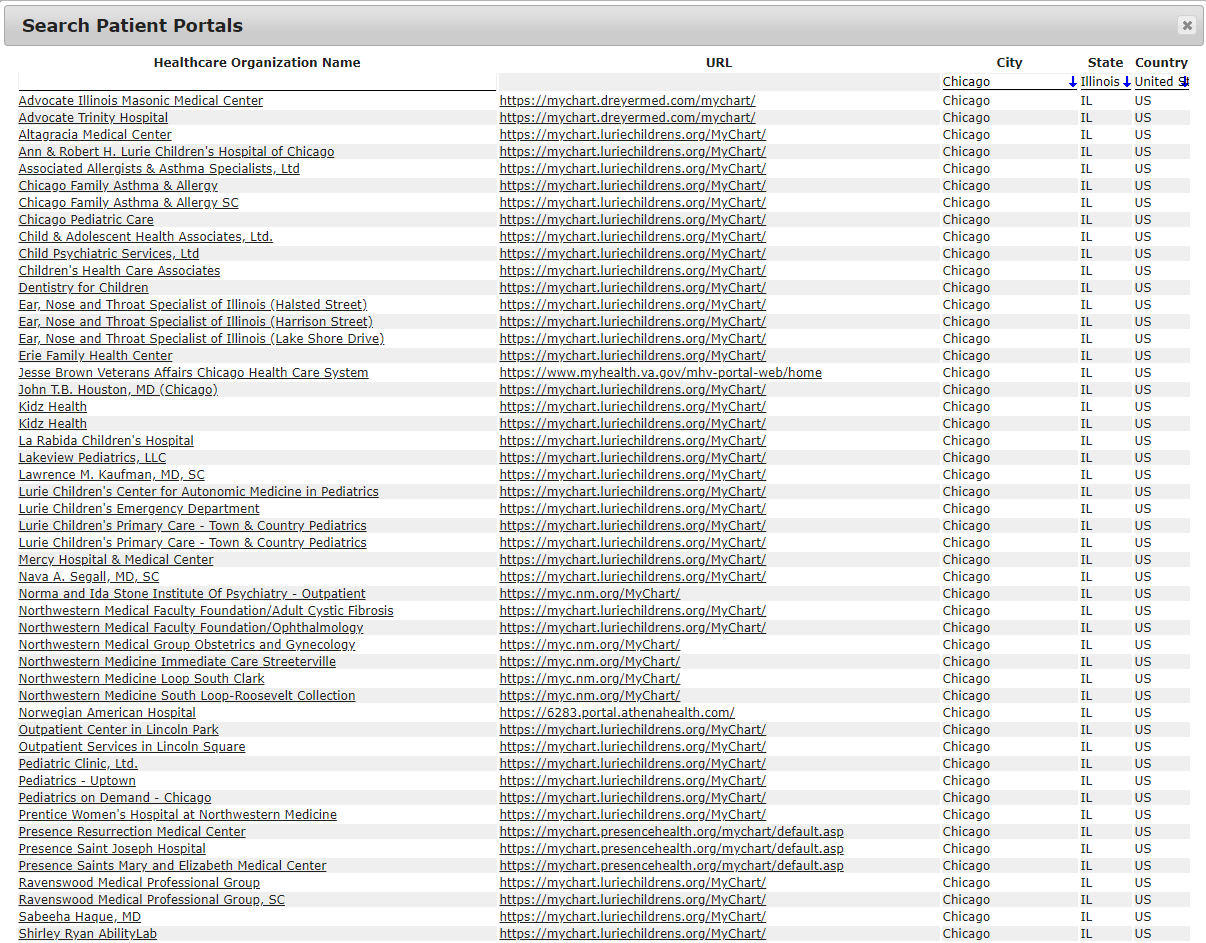

- Fetch My Records

- All Apps in iOS and Android

|

|

| |

|

January 15, 2014 – ISeeYouCare, Inc. rolled out the “Wounded Warrior eHealth Program” in March 1, 2014. Since that time,

thousands of disabled veterans have enrolled in this very special program. The program provides a free life-time Gold Level Subscription to

all disabled veterans. Furthermore, the program provides for the ability of seamless transfer of a veteran’s medical records to and from all

healthcare providers, be those associated with the Department of Veterans Affairs or the private sector. The management of ISeeYouCare, Inc.

believes it is the least that we can do for those who have sacrificed so much for our country. To our military servicemen and women, including

their families, we say “Thank You for Your Service and Your Sacrifice”!

|

|

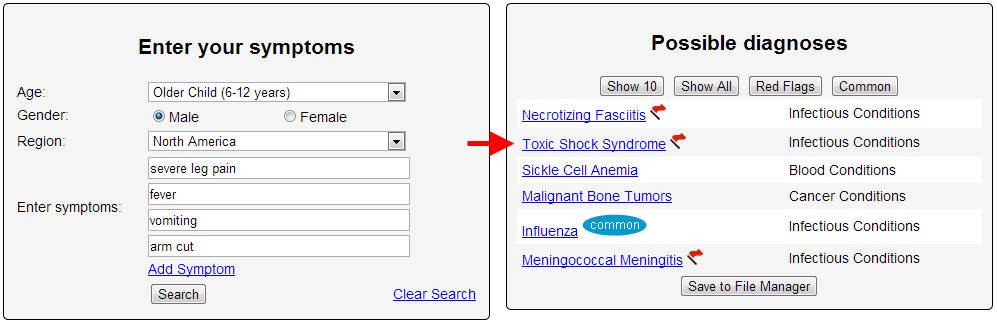

Rory, a 5-foot-9, 169-pound sixth grader cut his arm while diving for a basketball in the school gym. He began vomiting after midnight. By the time he saw the family pediatrician later that day, he was running a high fever, had severe leg pain, and his skin was not returning to normal color quickly when pressed.

The vomiting and fever suggested a stomach bug to the pediatrician, who sent him to the ED for fluids. A doctor in the ED thought he looked better after some IV liquids and sent him home with an antinausea drug. Rory’s body, however, was fighting an invader: known generally as sepsis.

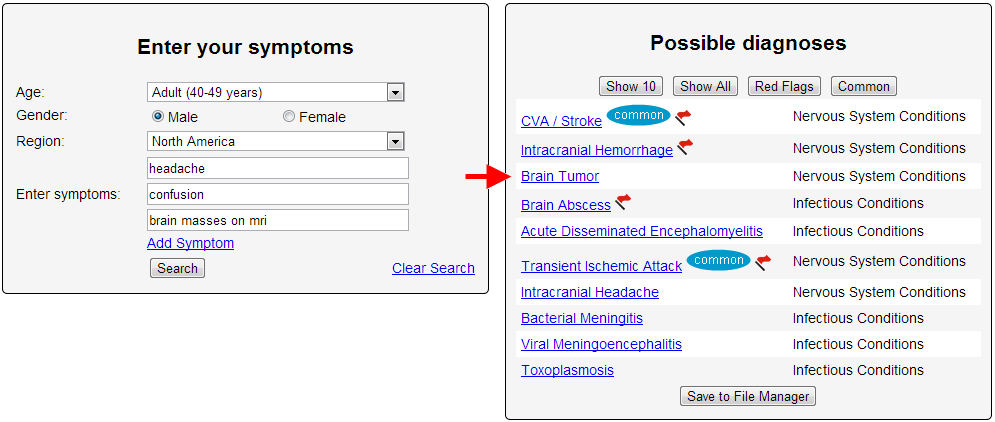

A previously healthy 44-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with a 2-day history of headache and word-finding difficulties. Neurological examination was normal but computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head revealed parietal and frontal masses concerning for malignancy or infection. Biopsy revealed evidence of vasculitis. Consultation with infectious disease, rheumatology, and neurology led to a provisional diagnosis of primary central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis. The patient was started on steroid and cyclophosphamide therapy and discharged after improvement in his symptoms.

Over the next month, the patient continued to feel well without a recurrence of his symptoms; however, serial brain MRI showed progression of the patient's lesions. Given his symptomatic improvement, the steroids were slowly tapered. A repeat MRI continued to show progression. Four months after the initial presentation, he re-presented to the emergency department after developing receptive and expressive aphasia and disorientation.

Imaging again revealed evidence of worsening lesions and repeat biopsy showed glioblastoma multiforme. The patient underwent resection and adjuvant chemotherapy followed by rapid clinical decline.

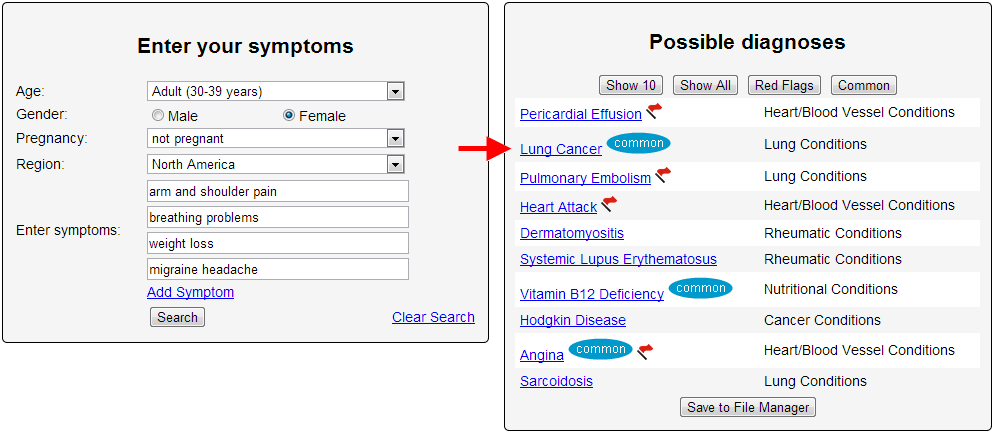

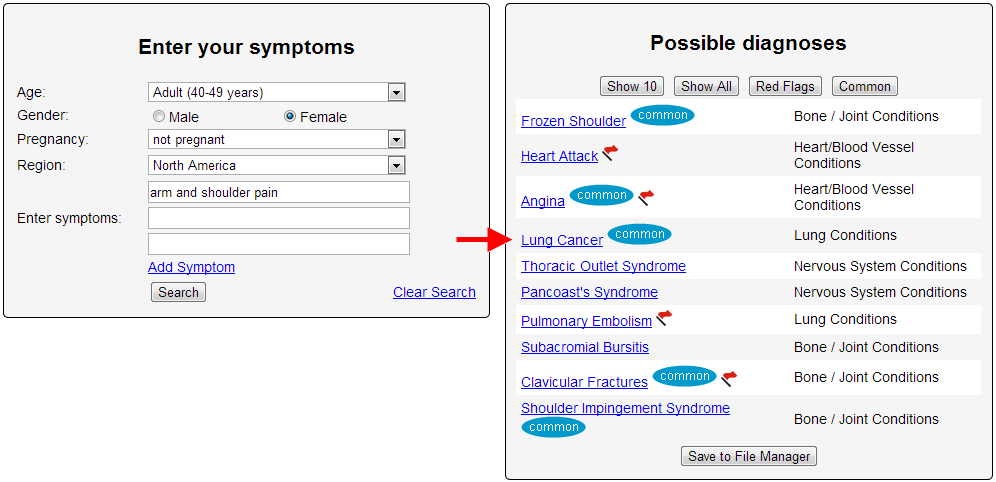

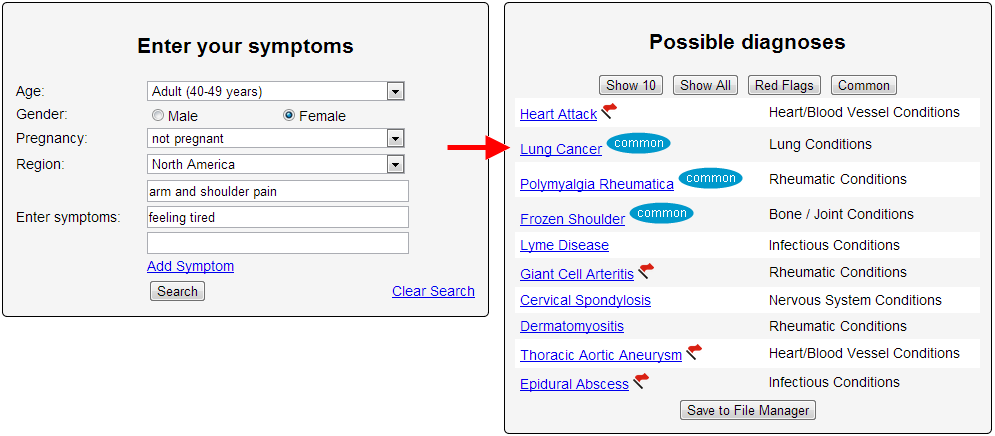

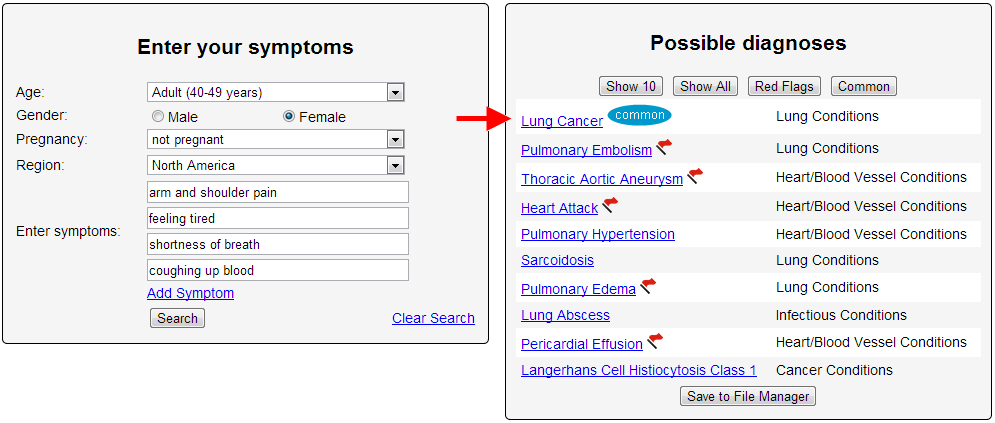

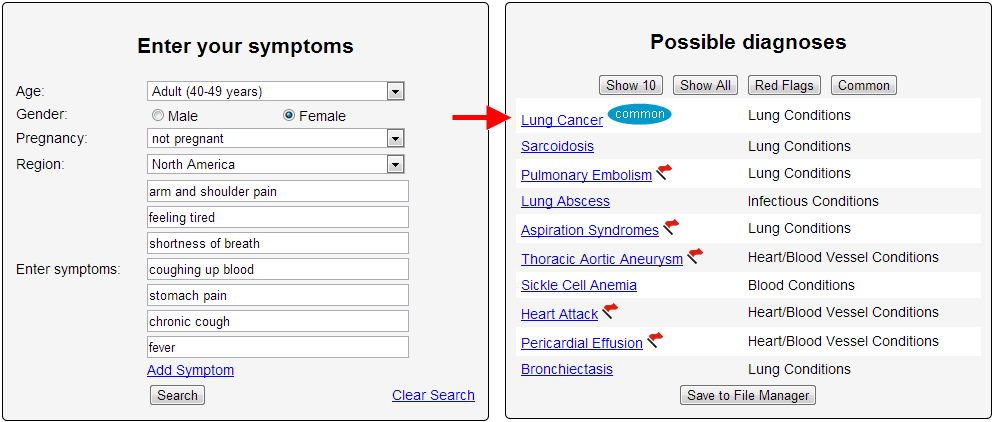

Lisa was suffering from migraine and weight loss for past one year but doctors could not correctly judge her problem. She also used to suffer breathing problems which made doctors think that she was a patient of asthma. It was in 2010 that Lisa suffered a problem in breathing. She went to doctor to get her arm and shoulder pain checked but she was found to be suffering from anxiety.

Three doctors were not able identify the lung cancer symptoms and told Dr. Lisa Smirl, 37, that she was suffering from anxiety and other minor ailments.Though the tumor got detected, it had become too late to save Lisa and she died in November 2012. The tumor had spread in her entire body and there was nothing much left for doctors to do. Lisa said, "I can't prove it, but I've no doubt my misdiagnosis was in large part due to the fact I was a middle-aged female".

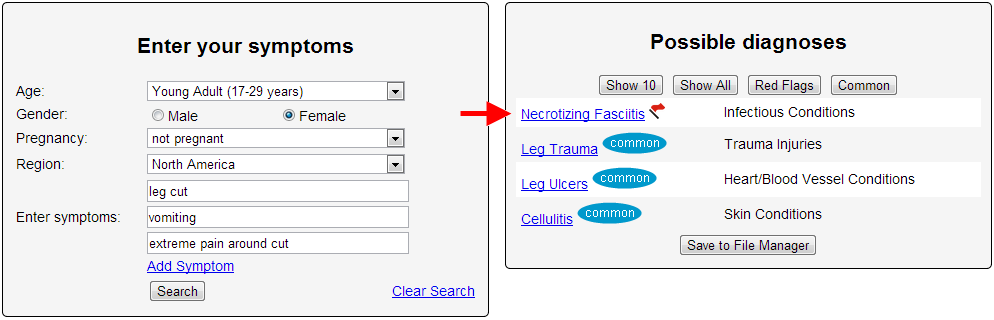

On May 1, Aimee was using a homemade zip line over the Little Tallapoosa River. She fell, hitting a rock in the stream below. She suffered a gash and was taken to Tanner Medical Center and received 22 stiches. The next day, she was in pain and couldn’t hold down food. She returned to the hospital and was given a prescription of Darvocet. The pain returned even worse the next day, so she was given a prescription for antibiotics. Again, she was treated and released.

The next day, she was extremely weak and went back to the hospital, where doctors diagnosed her with necrotizing fasciitis. Her father received a call from surgeons: We have to amputate her leg to save her. She eventually lost both hands and the foot on her other leg.

A woman who allegedly went blind after her physician misdiagnosed her is suing the physician for her injuries.

On May 8, 2012, Betty Joanne Bailey says she presented to Dr. Michael Gray Nunley with complaints of headache and blurred vision that came and went and lasted approximately 15 minutes. Nunley diagnosed her with visual migraines, even though she did not have a history of migraines, according to a complaint filed May 1 in Kanawha Circuit Court. Bailey claims nine days later, she presented to Charleston Area Medical Center with complaints of blindness in both eyes with a history of a four-day severe headache that began behind her right eye and right temple and was accompanied by blurry vision. She claims her pain subsided and she woke up blind in both eyes.

CAMC diagnosed Bailey with temporal arteritis and immediately started her on a high dose of steroids, but her blindness is permanent, according to the suit.

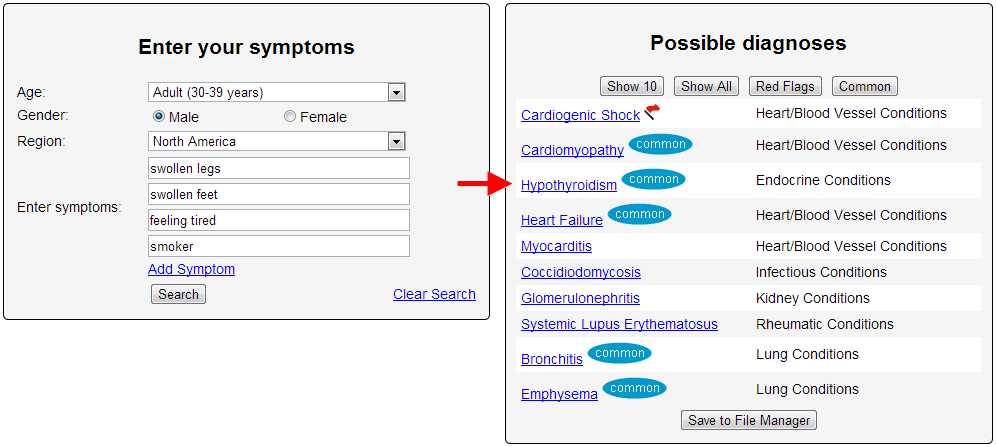

I started to experience a constellation of symptoms ranging from swollen feet and legs, lethargy, and carpel tunnel syndrome. I ached all the time and was cranky. Blood sugar was moderately elevated and triglicerides were through the roof. The doctors at the student health clinic diagnosed some facet of either cardiac, pulmonary or vascular disease because I smoked. They started sending me to specialists. Those specialists then acted on the diagnoses in their respective field based on the recommendation that smoking was the root cause of anything that may be wrong. After a huge number of tests, some invasive, each specialist was unable to pin down a diagnosis.

Over the next year I got worse. Then I came down with a simple head cold. I thought I was going to die. I went to an urgent care clinic in town and the first thing the doctor said to me was, "you have hypothyroidism." Hypo what? was my response. She immediately noticed that the outer third of my eyebrows were missing, a classic symptom of advanced and untreated hypothyroidism. My TSH was over 50. The problem that arose was twofold. One, doctors made the presumption that smoking was the cause of any issue. As soon as they focused in on that as a cause, they ignored everything else. And two, no one even considered hypothyroidism in a 35 year old male since it overwhelming affects women. I could have easily died as a result of at least five examinations by five specialists because they assumed rather than actually investigated.

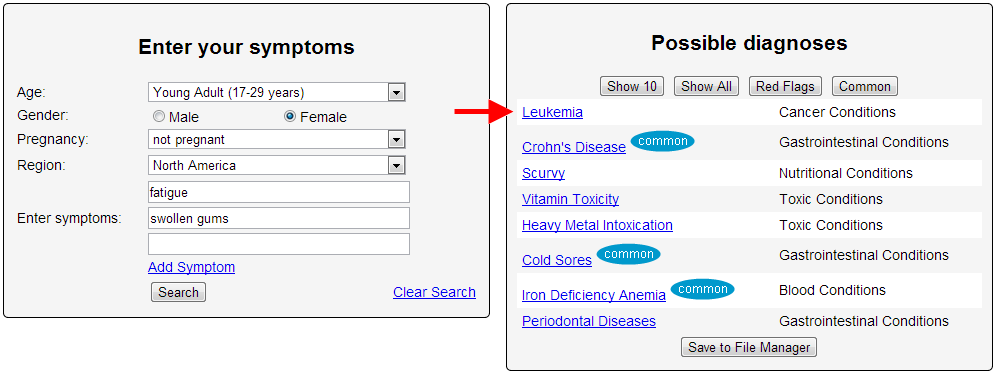

Birmingham 17-year-old Sophie Coldwell went to a walk-in medical centre on March 7 this year after feeling tired for a long time, the Daily Mail reports. She was diagnosed with fatigue, swollen gums and tonsillitis by a doctor who failed to recognise she was instead suffering from acute monoblastic myeloid leukaemia, a rare cancer.

Nine days later her breathing became shallow and raspy, prompting her parents to call an ambulance. Sophie lost consciousness on the way to hospital and died early the next morning. Her father Andy said they initially put her weariness down to additional schoolwork she had taken on in her first year at college. "As a father, I question everything I did and whether any more could have been done," he said. The fact it took everybody by surprise doesn't mean you still don't do that as parents."

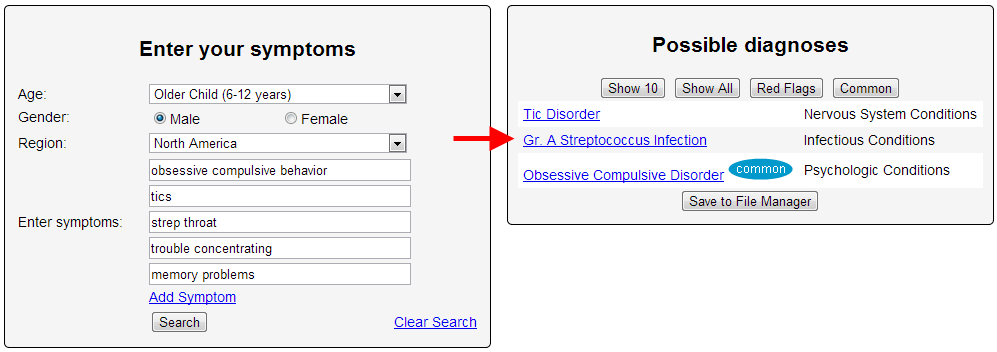

12-year-old Jason developed strep throat in 2011 and recovered after a round of antibiotics. However, according to his father Joe*, two weeks later and seemingly overnight, Jason developed obsessive-compulsive symptoms, tics, and separation anxiety and had trouble with concentration and memory. A straight-A student, he began failing tests and neglecting homework, later he had to leave the seventh grade. His pediatrician diagnosed him with Tourette’s Syndrome. He began treatment for Tourette’s but had no improvement in symptoms.

Months after Jason’s diagnosis, his parents stumbled upon information about a rare disease called Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infections (PANDAS), which described Jason’s symptoms and explained that they suddenly erupt after having strep throat.

Convinced that Jason had PANDAS (Group A Streptococcus), they saw a respected pediatric neurologist who said he didn’t accept PANDAS as a diagnosis because it had not been recognized by the majority of the medical community. But through their own efforts, they found a research study at the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, MD, for PANDAS patients, and Jason was accepted. Finally - 18 months later, in seeing his tenth doctor - he received the diagnosis of PANDAS and began experimental treatment.

Jason and his family went back and forth between Boston and Maryland, where he received trial doses of an immune-based therapy for six months. He has gradually improved, but because the disease progressed so far before the correct diagnosis and beginning treatment, Jason still suffers from many symptoms.

“If he would have been diagnosed rapidly and received the high dose of antibiotics necessary to treat it immediately, maybe it wouldn’t have done the damage that it did,” his father Joe said. “If you had a diagnosis faster and got treatment faster, it lowers costs and is more likely to prevent the illness from progressing.”

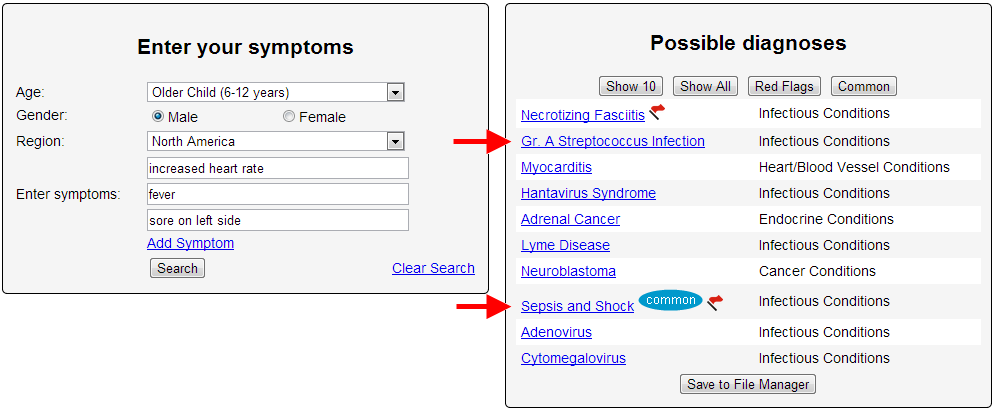

Eight year old boy, Richard de Souza from County Kildare was brought into the hospital with the complaint of developing a sore on his left side during his disease of Chicken pox in February 2011. The patient was taken to the Midland Regional Hospital where he was checked in the A&E Department. During examination of the patient, it was found that the patient had an infection and three day bed rest was suggested with the course of antibiotics. At discharge, the patient also had a high pulse and heart rate as well as high temperature. In such critical conditions, the doctor failed to diagnose his diseases and did not care for his other problems, including the increasing heart beat rate and acute temperature.

The patient took their boy home and on that evening the boy felt thirsty and became hallucinating. On the very next day, in the morning his mother called for an ambulance to take him to the hospital. When he arrived at the hospital, it was found he had suffered a severe heart attack and was declared dead. Later it was discovered that the boy had suffered from a streptococcal infection which developed into toxic shock syndrome. If the patient had been admitted into the hospital, this disease could have been treated easily and proper medical care could have been provided to the patient.

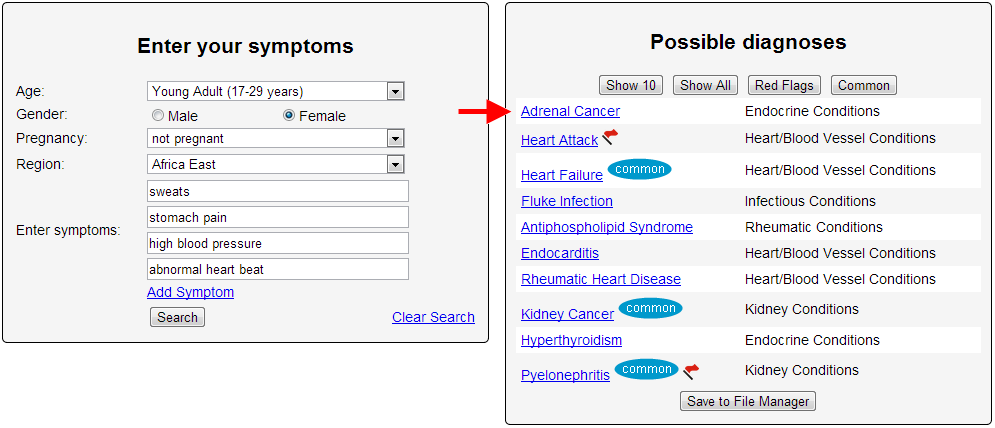

A 23-year-old gravid Ugandan female at 26 weeks was admitted to the maternity ward with sweats, abdominal pain, feeling of apprehension and palpitations. A diagnosis of pre-eclampsia was made and treatment with magnesium sulphate initiated. She was later transferred to intensive care unit for monitoring and control of blood pressure. Due to her labile blood pressures despite intravenous hydralazine and metoprolol, the pregnancy was terminated.

However, she continued to have labile blood pressures. Better control of blood pressure was achieved on oral prazocin and nifedipine.The patient was then transferred to floor and discharged home a few days later. An abdominal computed-tomography scan showed a solid lobulated right paravertebral mass superio-medial to the right kidney. An open adrenelectomy was performed and antihypertensives discontinued. Histopathology revealed a benign pheochromocytoma. The mother had good post-operative outcome; however the premature baby died 2 days later in the special care unit.

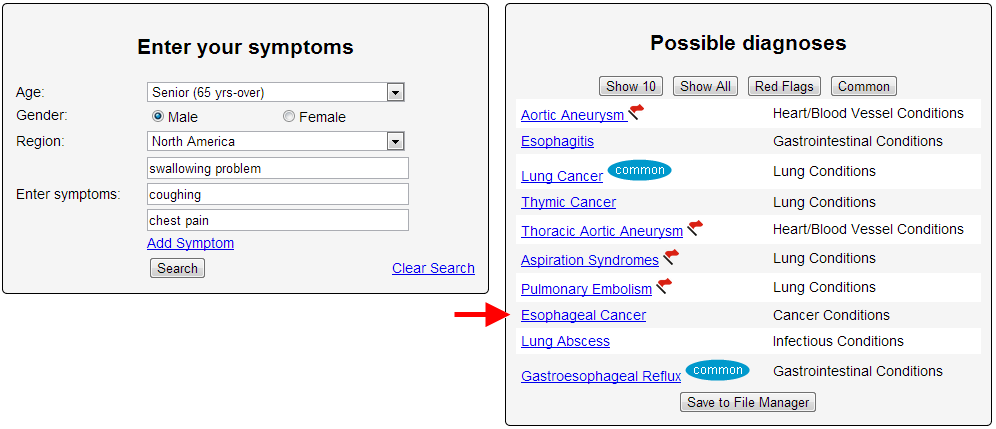

My wife's father had a esophageal cancer and was operated on in late 2011. In 2012 he was told at his 6 month check up he was cancer free he was overjoyed, excited to the point he framed the outcome on the wall.

Sept of 2012 he started to feel ill repeatedly, telling his Dr that he was having problems swallowing and coughing and chest aches while breathing. He had multiple CT Scans and Xrays. He was in the Dr Office and ER multiple times complaining of the same things. They said every scan was clear and that he was suffering from Bronchitis. His calcium was spiking into the 10,s and 9,s.

In April of 2013 my wife and I went to see him and he was deathly ill just by the look. We immediately called an ambulance and he begged to be taken to another hospital and we did. Upon arrival at the other hospital within 40 minutes they came back and told us that he was stage 4 cancer and was told terminal. They found this by comparing scans from the other hospital.

So he had no treatment or plan after his check up even though every sign pointed to him having cancer. Every time he was told it was Bronchitis giving him a false hope and not pursuing other options to treat the cancer that was slowly killing his body.

A BRISTOL hospital is being sued by a mother who claims her daughter suffered a serious brain injury when doctors failed to diagnose a rare form of meningitis.

Clare Day, of Horfield, now needs 24-hour support as a result of the damage caused to her brain by the tuberculosis meningitis in 2010 and is not capable of working or caring for her young son. Her mother Elaine Nikolovski is suing the trust that runs Bristol Royal Infirmary for the injury Ms. Day suffered and the care she will require for the rest of her life.

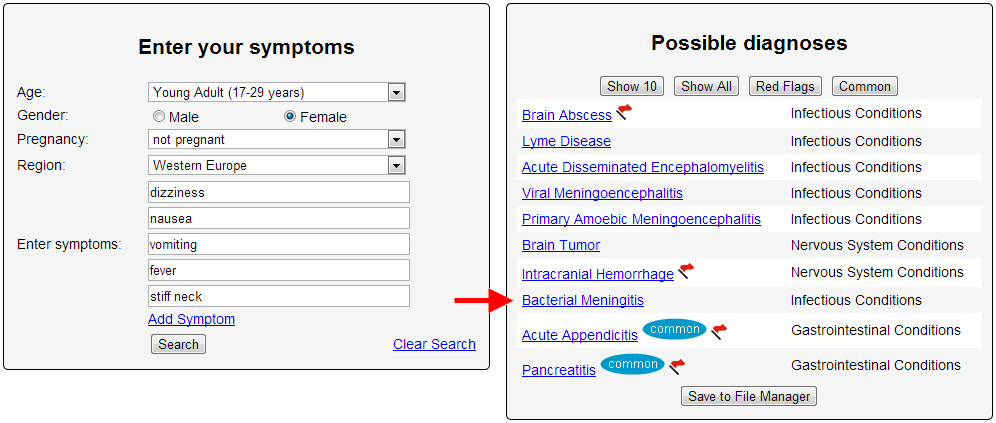

Ms. Day had suffered a head injury prior to first seeking medical attention and her symptoms of dizziness, vomiting and nausea were initially put down to concussion as a result of banging her head.

But her solicitors argue that, when her symptoms continued, more tests should have been carried out to see whether meningitis was a factor.

They claim that having attended the emergency department at the BRI three times, doctors should have paid attention to symptoms of a temperature and stiff neck and that a lumbar puncture, a procedure to collect a sample of spinal fluid, should have been carried out to check for meningitis.

The claim filed with the High Court suggests that if Ms Day's care had been managed properly "on the balance of probabilities she would have made a full recovery from TB meningitis and avoided the brain injury".

Instead, when her condition deteriorated and she was finally admitted to hospital and diagnosed with the form of meningitis caused by the tuberculosis bacteria, it was too late and she suffered the permanent debilitating brain injury.

Speaking on behalf of Ms Day's family, Julie Lewis, a partner and medical law expert at Irwin Mitchell's Bristol office, said: "University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust has admitted responsibility for a delay in diagnosing tuberculosis meningitis when Clare was admitted to Bristol Royal Infirmary in March 2010, which ultimately led to her suffering a severe permanent brain injury.

"We are now working with the trust to secure a lifetime care package for Clare, as she needs 24-hour support from a team of live-in carers, as well as specialist equipment, rehabilitation and therapies to improve her quality of life as much as possible.

"We hope that improvements have now been made within the trust in recognising the symptoms of tuberculosis meningitis, to show that lessons have been learnt and to prevent anyone else from suffering such a devastating injury in future."

Deborah Lee, deputy chief executive at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, which runs the BRI, said: "It is very disappointing when patients are not satisfied with the quality of care we have provided. As this case is now subject to legal proceedings, it is inappropriate for us to make any further comment at this time. We are committed to resolving this."

The symptoms I initially presented with were both myriad and confusing. I initially encountered notable weakness in my arms and shoulders in June of 2000. My general practitioner at the time took my concerns seriously. Although he did not mention the possibility of lung cancer, I later found in my records this observation “I would like to do a chest x-ray to make sure that there are no chest lesions which would be very unusual in this young, nonsmoking woman, causing brachial plexus problem.” He was aware of something I was not: It is possible to get lung cancer even if you never smoked.

The source of my weakness was not resolved (although I now believe it was the manifestation of a paraneoplastic syndrome — potentially an early harbinger of cancer), but frequent sinus infections and a general sense of malaise prompted many return trips to the clinic.

As a young woman in her forties who spent too much time at the doctor, it was suggested at one point by a neurologist who was following my complaints of upper body weakness, that I might be a hypochondriac — from a confidential note in my records dated March of 2002.

I also had a new complaint; shortness of breath and occasional hemoptysis. After a second chest x-ray came back negative for any finding, the new general practitioner diagnosed me with adult onset asthma. It was March of 2003.

Over the next year and a half, my ‘airway disease’ was monitored every few months. The weakness in my arms and shoulders continued to progress, and I began to see a physical therapist. By January of 2005, I was experiencing discomfort in my upper left abdomen, a chronic cough, and when I lay down, my left lung sounded like an old saddle. By March I was running a fever and coughing up copious amounts of bloody phlegm and I was diagnosed with pneumonia.

However, several weeks of antibiotics failed to clear up my symptoms, and a subsequent chest x-ray confirmed that a large mass remained in my left lung. This was followed by a chest CT scan and a differential diagnosis: unresolved pneumonia, a fungal infection, or a neoplasm; possibly malignant. My doctor scheduled a biopsy, and in the days leading up to it, I read what I could about lung cancer. Next week, hearing the words, “You have cancer.”

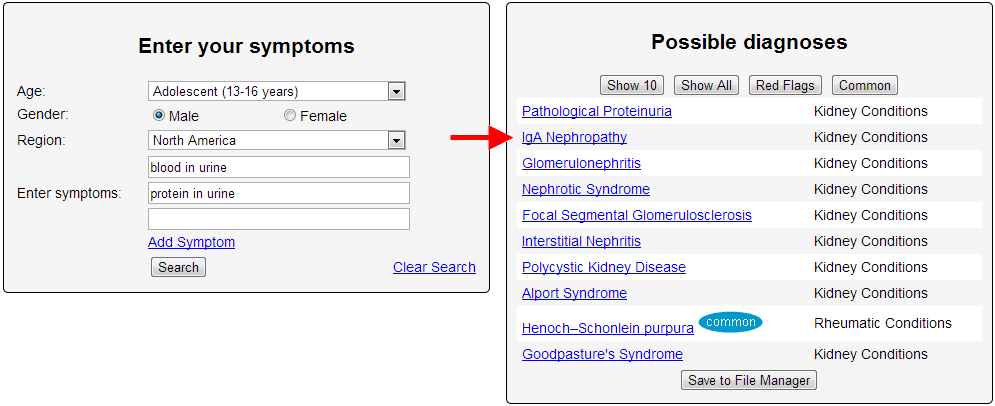

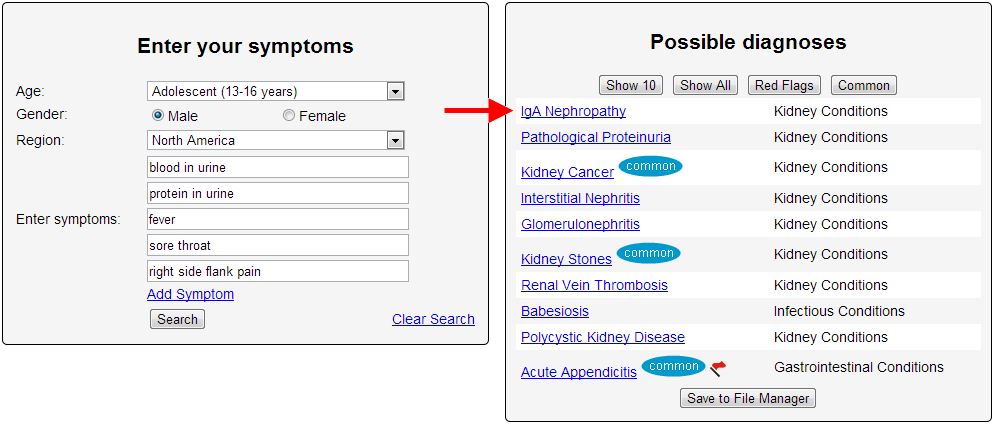

Ms. P, a urology PA, assisted the on-call urologist and treated patients when the physician was not in. One case was Mr. E, a teenager who had presented six weeks earlier complaining of blood in his urine. The urologist, Dr. B, was in that day and handled the case, but Ms. P was surprised when she saw the teenager back in the ED only a month and a half later. Before speaking with the patient, Ms. P reviewed the clinical notes from his previous visit. Laboratory results revealed both hematuria and proteinuria. Dr. B had noted the diagnosis as a urinary tract infection (UTI) and prescribed antibiotics, which apparently had failed to work.

The patient was now complaining of continued hematuria as well as a fever, sore throat and right flank pain. Ms. P questioned both the patient and his mother to determine whether he'd taken his antibiotic properly. Mr. E had followed the protocol correctly. Ms. P decided to call Dr. B. She quietly questioned whether the original diagnosis of a UTI was correct.

Ms. P described Mr. E's new symptoms, and explained that the antibiotic had not helped. The urologist told her to prescribe a different antibiotic. “What about the new symptoms?” Ms. P asked. “Those are consistent with a UTI,” replied Dr. B. “Don't worry about it.” “But is there any other possible diagnosis we should consider?” pressed Ms. P. “It's a UTI,” said the physician. “If it doesn't resolve, he'll be back and we can question it then.”

Two years later, Mr. E returned to the ED, complaining that he was spitting up blood and had pain in his side below his ribs. Tests showed that his kidneys were not functioning. A renal biopsy revealed that the patient had late-stage immunoglobulin A nephropathy, a severe kidney disease that would require hemodialysis three times a week. A specialist concluded that the kidney disease had progressed too long without treatment, resulting in irreversible kidney damage.

Mr. E and his mother found an attorney who encouraged them to sue the urologist and Ms. P for failing to diagnose nephritis during the two ED visits. Both Ms. P and Dr. B ended up settling out of court. The plaintiff received a sum close to the limits of their respective liability coverage.

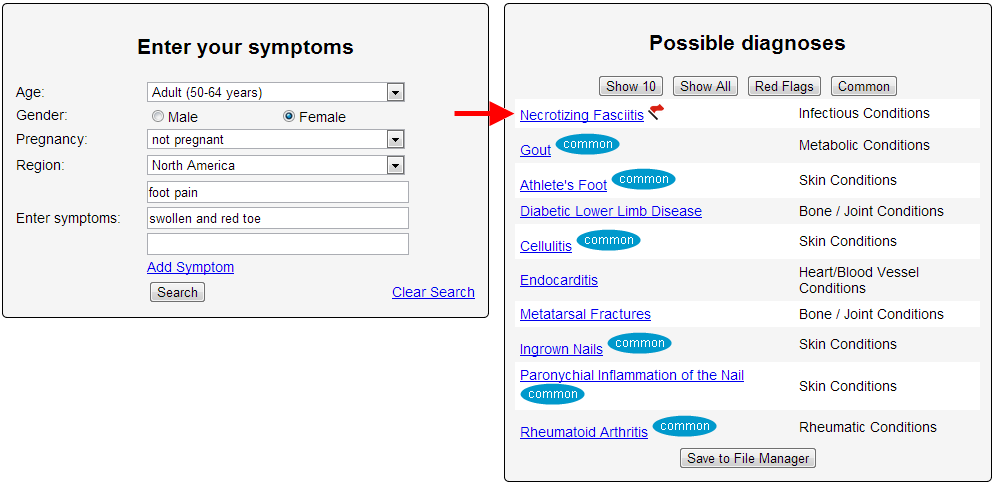

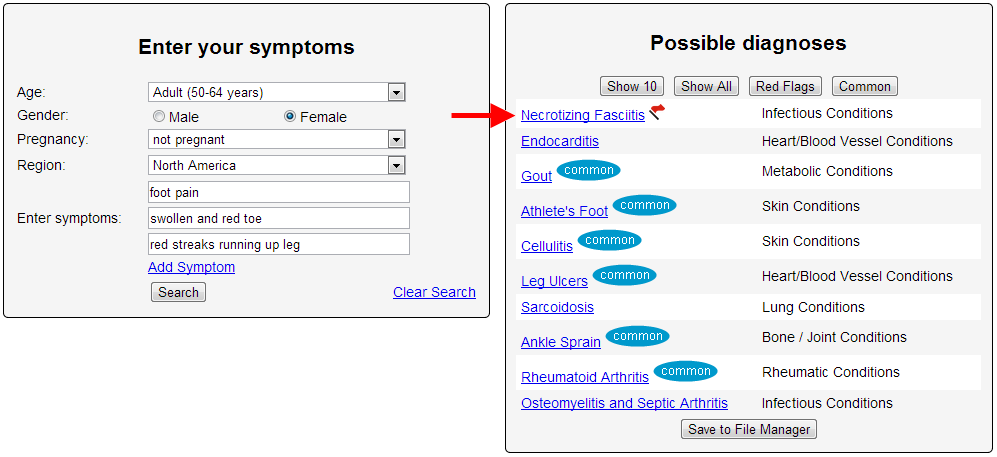

Sherril Ismay went to an urgent care center in Grand Junction, Colo., one night in January 2009 to have her right foot examined. She didn't think she had a serious problem, but it was swollen and sore, and red around the joint of her big toe. The physician assistant who examined her gave her a diagnosis of gout, prescribed pain pills and a gout medication, and sent her back to the hotel where Ismay, then 57, was staying. (At the time, she was working as an oiler maintaining heavy equipment on a gas pipeline construction site.)

After two days in bed with worsening pain, Ismay got up one morning and saw red streaks running up her leg past her knee. She knew right away it could be a sign of serious infection. A co-worker took her to the urgent care center. The doctor on duty examined her, and the next thing she knew, she was in an ambulance on her way to the hospital.

It turned out that Ismay had necrotizing fasciitis, commonly referred to as flesh-eating bacteria, a potentially life-threatening infection that destroys soft tissue. Over the months that followed, doctors amputated more and more as they struggled to contain the infection. Her leg now ends an inch below the knee. She had to give up her job, which required a lot of walking over uneven ground, and now lives with her sister. "I was so strong and healthy," she says. "I never had any idea this could happen to me."

Ismay’s lawyer, who filed a malpractice lawsuit in January, says that by not taking proper steps to diagnose Ismay’s condition, whose symptoms were consistent with both gout and infection, the physician assistant breached the standard of care. The PA should have withdrawn fluid from the joint to look for infection, says Natalie Brown, a personal injury lawyer with Leventhal, Brown & Puga in Denver. "More important, she never told her to follow up with a physician or look out for signs and symptoms of infection," says Brown. "I don’t think infection was even on her radar."

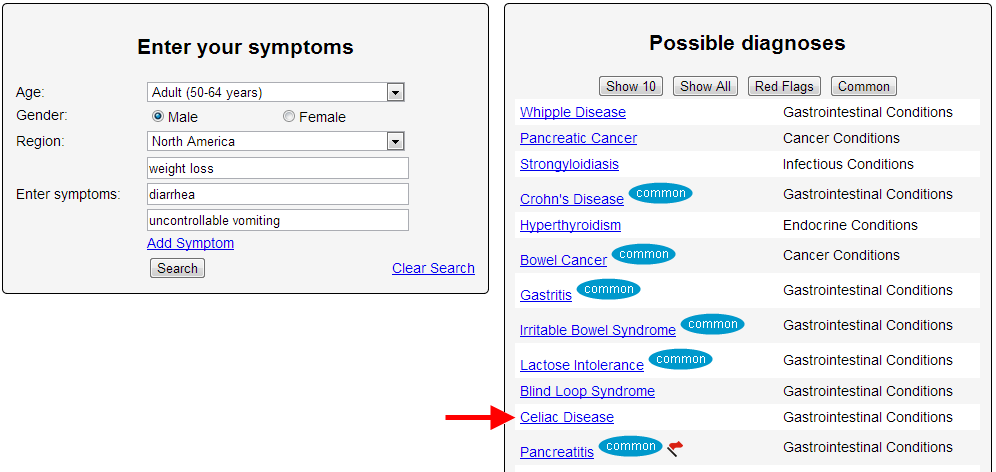

Tom Hopper, at 64, began “losing weight”. A few months later he was crippled by episodes of “uncontrollable vomiting” and “diarrhea”, sometimes for upward of seven hours, which left him dehydrated and delirious. Cramps in his legs were so painful that he often couldn't stand up. Over the next five months, Hopper was hospitalized five times and received various diagnoses. During his first emergency room visit, doctors concluded he had food poisoning. When he returned after the next vomiting attack a few weeks later, physicians ran a series of tests but found nothing.

And on it went, month after month. Different doctors had different theories. Some thought he had a virus. Others thought he had a digestive disease. One even recommended that he have his gallbladder removed. "Let me think about that," Hopper wisely responded. The next specialist suggested shaving off part of an intestinal muscle to create a larger opening to his bowel. This time Hopper agreed. "When I woke up from the anesthesia," he says, "the doctor told me I'd never have to see another doctor for the rest of my life.“

But that prediction was premature. On a flight to Boston just a few days later, Hopper began vomiting. Once the plane landed, medics rushed him to Massachusetts General Hospital, where he stayed for 11 days. At Mass General he underwent another round of extensive testing, but nothing proved definitive. Then one internist, Michael Barry, M.D., noticed that as soon as Hopper switched from a liquid diet to regular hospital food, he got sick. Barry spent an hour at Hopper's bedside, asking detailed questions about his extended family's medical history, including where his ancestors came from.

A DNA test confirmed Barry's suspicions: Hopper had a gene marker that made him especially susceptible to celiac disease, a fairly common autoimmune disorder characterized by an inability to process gluten. "By then I had seen dozens of doctors and six digestive specialists," recalls Hopper, " but none apparently understood the importance of looking at my diet."

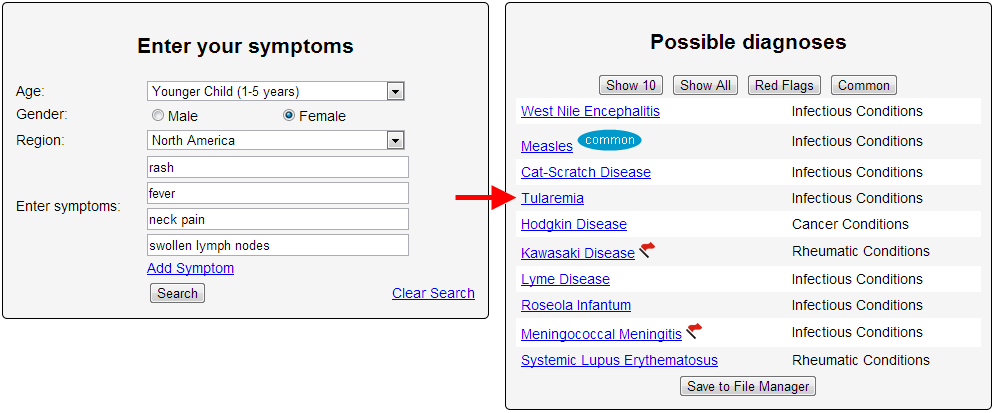

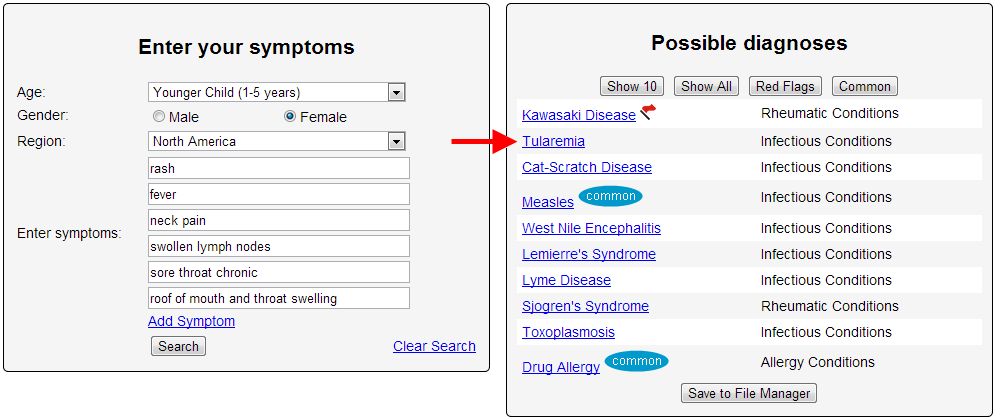

Eva spent Memorial Day weekend swimming in Birdwood Creek and the Interstate lakes near Hershey. Afterward, her mother, Jennifer Nutter, noticed a tick on the left side of Eva's neck.

Jennifer said she pulled the bug off and forgot about it. Soon after, Eva developed a rash and fever and complained of neck pain. The lymph nodes behind her ear and by her clavicle swelled.

Jennifer, a registered nurse, became concerned Eva might have meningitis. She took her to Great Plains Pediatrics in North Platte, where another tick was found in Eva's hairline near her left ear.

"The tick wasn't imbedded completely, but it was evident it had been there for a while," Jennifer said. "The site was infected. There was a red, swollen area about 3 inches wide that was hot to the touch."

Cultures were done, and Eva was put on an antibiotic and sent home. When she started complaining about a sore throat a few days later, Jennifer took her back to the pediatrician's office.

"By then, she had pustules on the roof of her mouth and her throat was swollen," Jennifer said. "The areas where both ticks had bitten her were even more inflamed, and the skin around them was peeling."

More cultures were performed and Eva was put on another antibiotic, which she caused an allergic reaction. Ultimately, Eva was taken to the Children's Hospital and Medical Center in Omaha.

On June 6, she was diagnosed with tularemia, also known as rabbit fever or deer fly fever. Because of Jennifer's nursing background, officials at the children's hospital agreed to let her treat Eva at home with IV fluids. Eva received doses of Gentamicin three times a day for nine days and is feeling better, Jennifer said.

The biggest problem with both tularemia and Rocky Mountain spotted fever, another tickborne disease, is that they are so uncommon they are often overlooked.

"Doctors often misdiagnose them and prescribe the wrong antibiotics to treat them," Safranek said. "The good news is they are preventable."

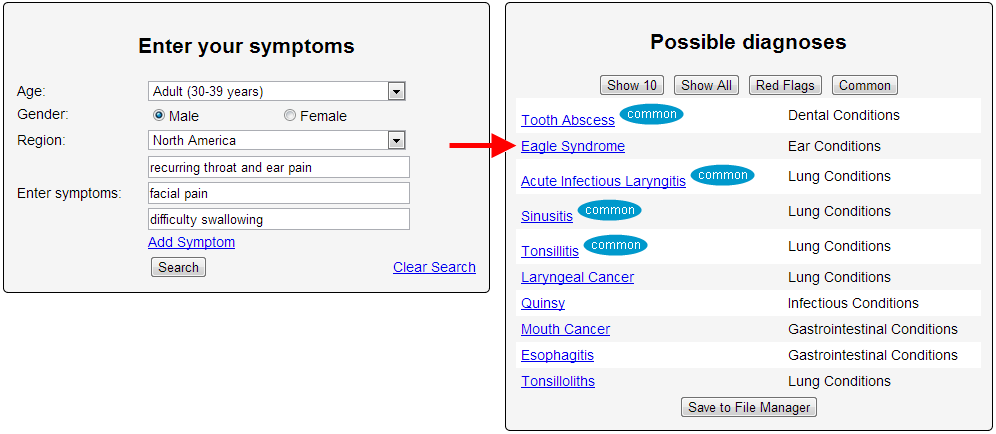

Carl Holt, 34, was subjected to two years of GP and hospital appointments suffering constant throat pain after he fell ill on a family holiday in July 2010, visiting doctors 150 TIMES. Despite hospital appointments and visits to his doctor up to SIX times a month, medics could not work out what was wrong with him. Carl feared he had the symptoms of cancer and was so worried he even contemplated suicide. But after researching his symptoms on the internet and watching videos on Youtube, he found out about a rare condition called Eagle Syndrome. Remarkably, despite telling doctors about the disease, Carl was never tested for it at three separate GP practices or the University Hospital of North Staffordshire. Carl then decided to pay for private care at Salford Hospital in Greater Manchester in October last year and was finally diagnosed with the rare medical condition within MINUTES of his first visit. He slammed the NHS for failing to spot the condition despite the staggering amount of GP and hospital appointments. Carl , who lives in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffs., fumed: “People started questioning my mental health because I was always at the doctors, yet they could never find out what was wrong with me. “Through research, I found out about a condition called Eagle Syndrome, which seemed to tick all the symptoms I was suffering. “I saw videos about it on YouTube and Googled it but even though I told my doctors about it, no-one would believe me or test me for it. “It was so frustrating. The pain and the symptoms wouldn’t go away but doctors just weren’t interested and would just tell me to take painkillers. “I even paid to go and get second opinions privately but every time I did it was the same doctors I had seen on the NHS. “Because I had a sore throat for so long I thought I had throat cancer. “At the time I was on the cusp of becoming a dad and I worried I would never get to see my daughter. “When I finally got the diagnosis, I felt a lot of relief. “I saw a consultant in Manchester and within minutes of looking at my CT scan he confirmed it was Eagle Syndrome. “I was appalled – it just shows that if all the other doctors listened to me instead of fobbing me off then I would have been diagnosed two years earlier.” Symptoms of Eagle Syndrome include throat and ear pain as a result of small bones to the rear of the throat becoming calcified, or hardened. Sufferers often have the feeling something is stuck in their throat and have difficult swallowing as well as facial pains.

Carl, who spent a staggering #10,000 on trying to get a correct diagnosis over the two years, is now being treated as a NHS patient at Salford Royal Hospital. He had anti-inflammatory injections on March 8 this year and has a follow up appointment later this year to see if he needs painful surgery or more injections. “I went from 18-stone, physically fit, playing football twice a week and leading a very active life, to simply going to work, then coming home and going to sleep. “I had injections that went straight into the styroid ligaments. It was the first time in over two years that I didn’t have a pain in my throat. “I still don’t feel 100 per cent, I would say I’m at 80 per cent now. “I’ve spent #10,000 over the two-and-a-half years but at least I have answers now.”

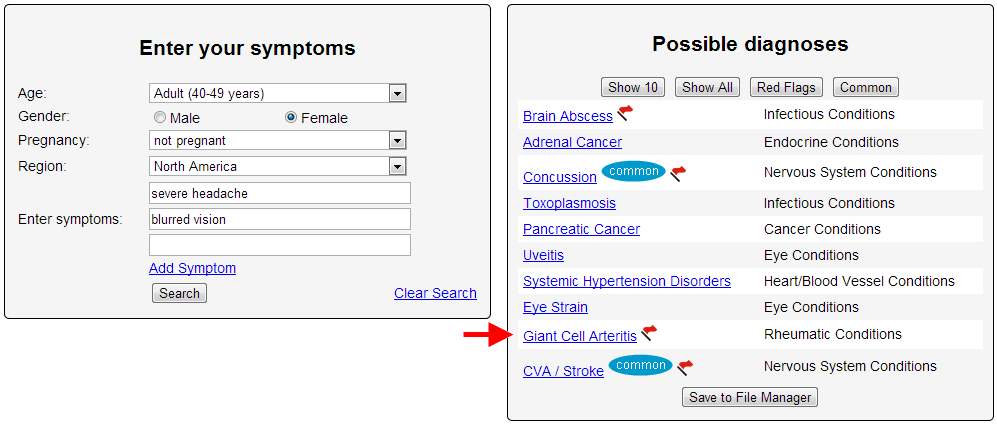

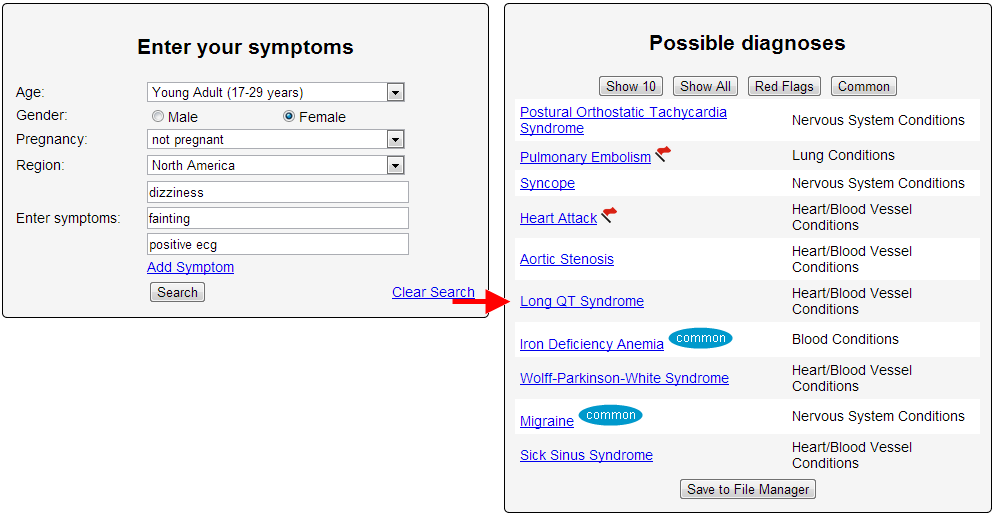

I became ill and it took seventeen weeks of investigations by five hospitals to make a diagnosis. I am told that the variable manner in which Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA) develops symptoms can make it indistinguishable from many other diseases and thus poses a diagnostic problem for doctors.

The NHS doctors that took charge of me all seemed hard working, competent and caring. Three stand out by their interrogation of me in respect of symptoms and potential causes of my non-diagnosed illness - at that time.

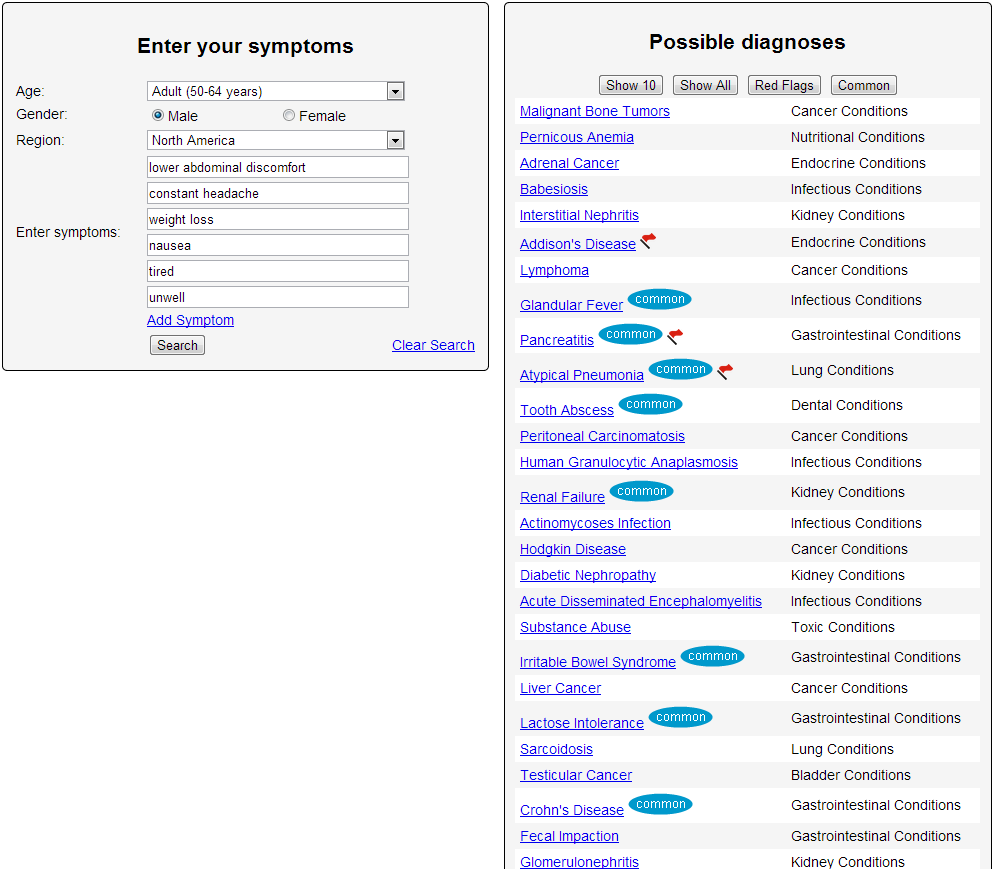

Is GCA hard to diagnose though? I Googled ‘the world’s best medical diagnostician’. The result took me to a software package called Isabel. I used this software to investigate my symptoms as they had developed over several months. There are some changes in my descriptions ('felt like a hangover' for example I changed to tired and unwell) but I have followed a document I gave to the first consultant who dealt with me in the fourth hospital rather than modify description with the benefit of hindsight.

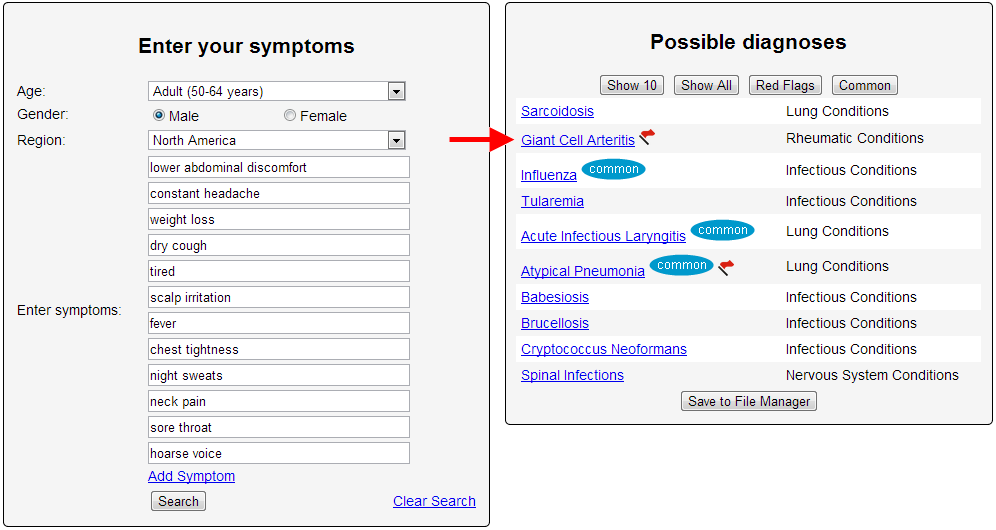

WEEK ONE: Whilst on holiday in France, the symptoms of my illness were; lower abdominal discomfort, constant headache, weight loss, nausea, tired and unwell. Feeding this data into ‘Isabel’ results in a list of almost 40 illnesses.

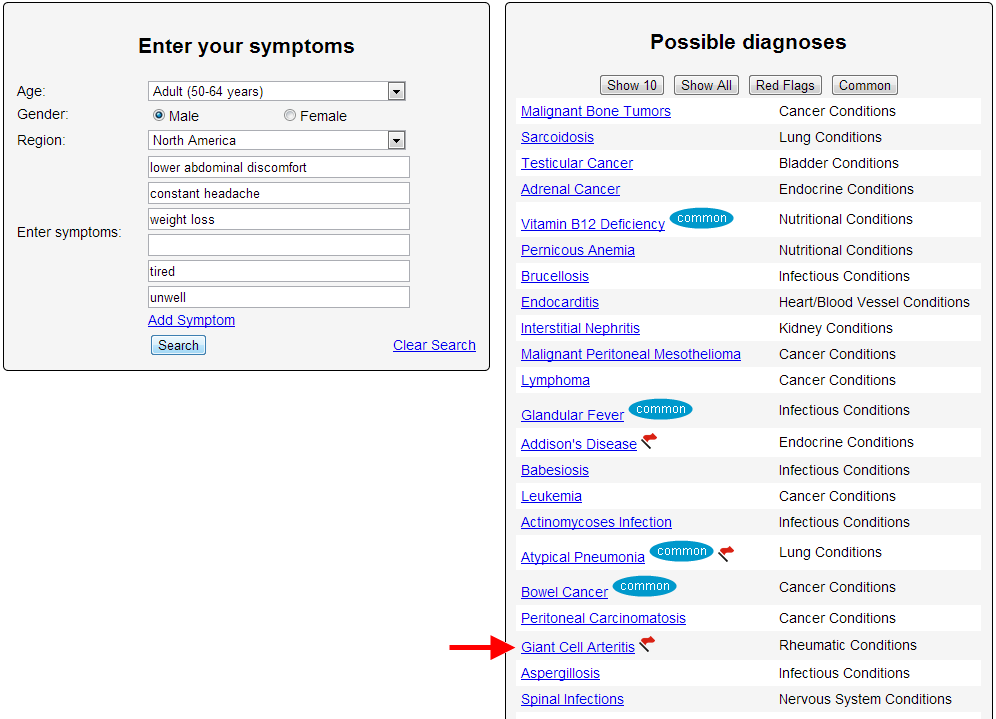

This demonstrates the importance of thinking carefully about what symptoms you have and how best to describe them. I was not nauseous, (feeling as though one is about to vomit) this was best described by the word I had already used - unwell. Removing nausea resulted in Isabel listing GCA at number 20.

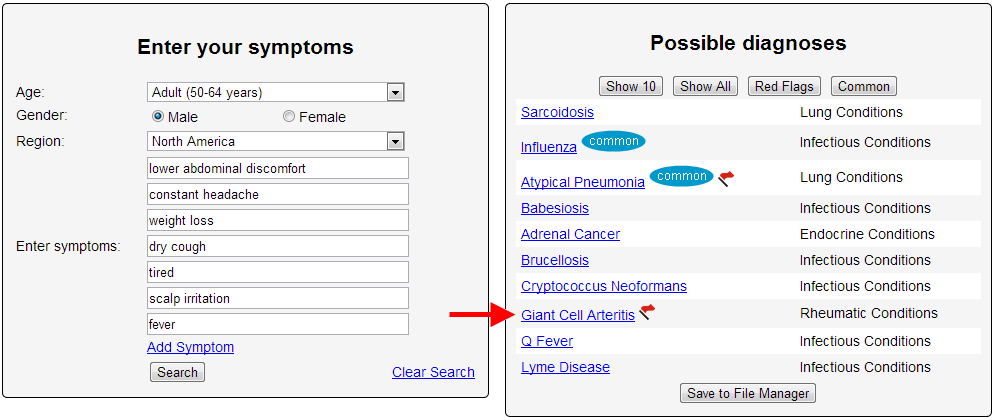

I had three symptoms that I did not describe but were present they were dry cough, scalp irritation and fever. My wife had noticed the infrequent cough which I had for several weeks but it had not registered with me, the scalp irritation I did not link with my illness and I simply forgot about the high body temperature I had - 37.8 deg C. Removing nausea and adding dry cough, scalp and fever puts GCA at number 8 in a list of possible diseases.

WEEK FOUR: At week four I had the following additional symptoms; chest tightness, night sweats, neck pain, sore throat and hoarse voice. With this Isabel puts GCA at number 2 in a list of over 30 diseases.

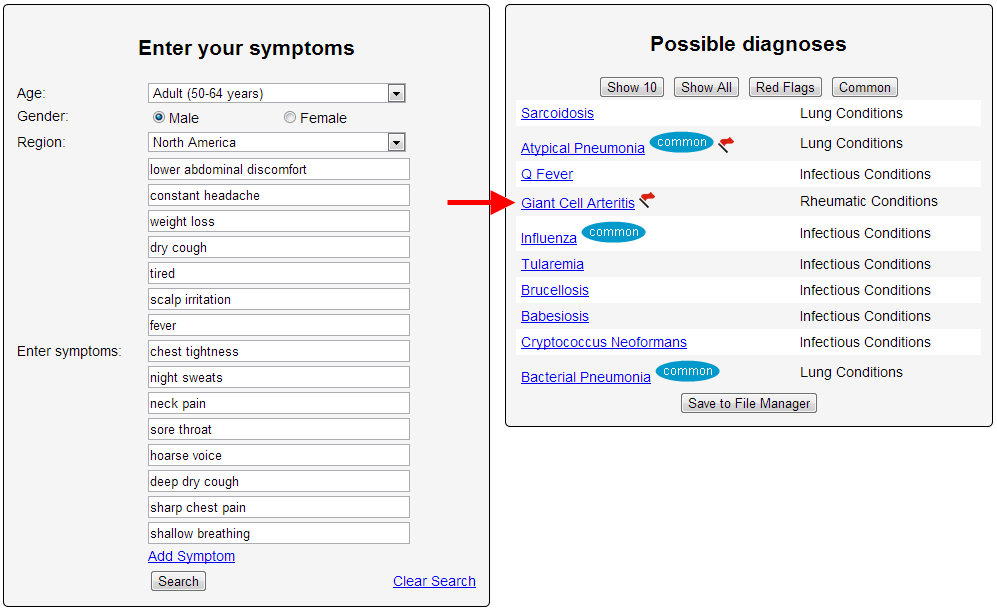

WEEK SIX: I return to England where I am admitted to a southern hospital (hospital one) for three days. I had acquired further symptoms of deep dry cough, sharp chest pain and the need to take shallow breaths to avoid coughing. Isabel suggests 41 possibles with GCA at number 4. This hospital discharged me with a presumptive diagnosis of pneumonia.

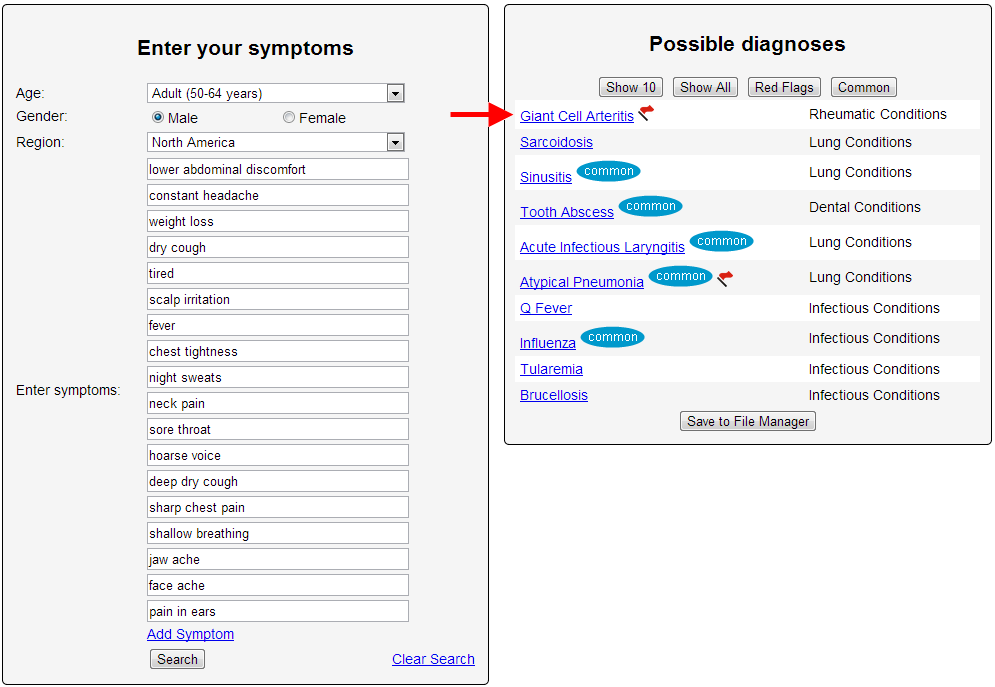

WEEK SEVEN: I went to A & E at a district hospital in northern England (hospital 2). With further symptoms of jaw and face ache and pain in my ears. Adding these to the list of symptom at Week Six - Isabel predicts GCA at number 1.

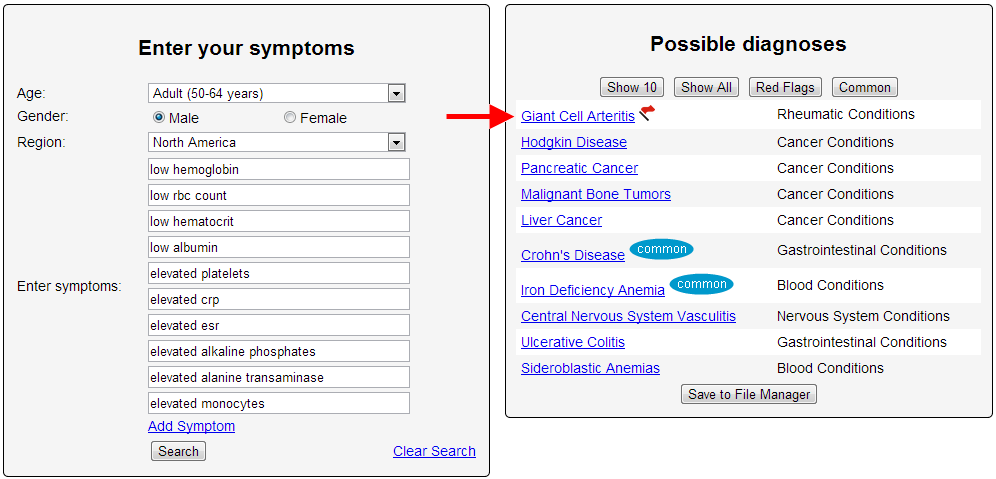

WEEK EIGHT: I was admitted to a local district hospital (hospital 2). Inserting the blood results into Isabel, which were; low Hb, RBC, HCT and albumin; and elevated platelets (598), CRP (244), ESR (94), Alkaline Phosphates (256), Alanine transaminase (122) and Monocytes (0.88). Disregarding my physical symptoms and using only the blood results, Isabel lists the possibles as number one GCA. Isabel predicts my condition by two different routes; patient described symptoms and by hospital performed blood tests. I think this is very impressive.

At this point I had been seen by two doctors in France, at least six in the southern hospital, two locums and my GP at his surgery and at the local district hospital by two doctors in A & E and at least four doctors in their assessment unit. None of these doctors could make a diagnosis even though they had the aid of X-Rays, CT, MRI and echo scans and twelve days in hospital.

It took almost 5 weeks more as a private patient (hospital 3) and then a major city hospital (hospital 4) and then by a separate team from the fifth hospital to make a diagnosis. The cost to the NHS of my stays in hospital and diagnostic procedures was in excess of £20,000. The use of Isabel in the early stages of my illness would have saved 95% of these costs and prevented some irreversible damage to my arteries.

“I have no connection with Isabel healthcare, this commentary was volunteered by myself.” - Steve

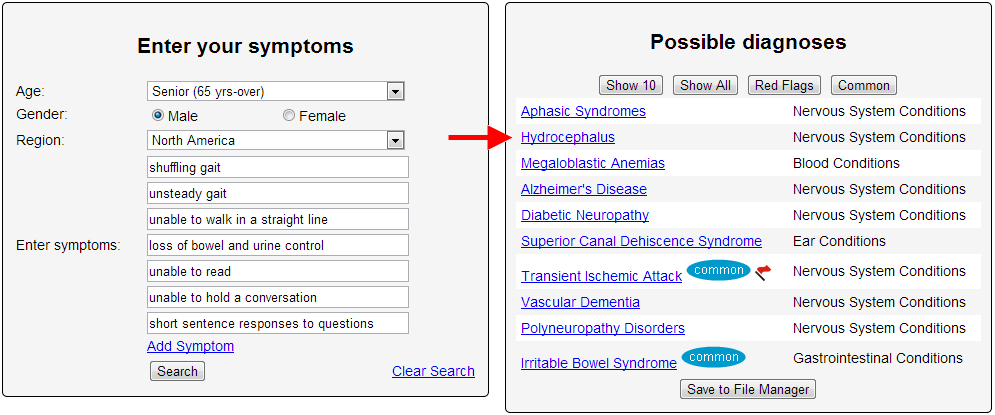

Jim Lambert got up in the middle of the night five years ago in his Chelmsford home to use the bathroom and fell flat on the floor. A cascade of health problems ensued that were as a nightmarish as they were mysterious. The 72-year-old retired hospital fund-raiser lost his ability to walk in a straight line, and instead shuffled with an unsteady gait. He lost control of his bladder and bowels. An eloquent speaker and voracious reader, he suddenly couldn’t read or hold a conversation, and answered questions with short sentences. Lambert’s family physician diagnosed him with Alzheimer's disease and prescribed medication. Skeptical of the diagnosis, Lambert’s wife relentlessly sought second and third opinions: A neurologist also thought it was Alzheimer’s, and a psychotherapist disagreed with that diagnosis but was unsure what the problem was. Meanwhile, Lambert continued to decline. His wife, Terrie, who had been bathing and dressing him, developed serious health problems of her own, and was no longer able to care for him. Eventually unable to move, Lambert ended up in a nursing home, slumped most days in a wheelchair.

But Terrie didn’t give up on her three-year odyssey searching for help for her husband and ultimately discovered a specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital who diagnosed Lambert with a little-known brain disorder, called normal pressure hydrocephalus. Known as NPH, it is believed to plague more than 300,000 Americans, many of whom don’t realize that the disorder’s hallmark symptoms — a distinct, wide-stance shuffling gait, dementia, and incontinence — can be treated and often reversed.

“It’s like I was reborn,” Jim Lambert, now 77, said in an interview, as he described the stunning reversal of most of his symptoms within days of treatment last year. He is back to reading his beloved military history books, chatting and joking, and mostly walking normally — only a bit unsteady on uneven ground, where he uses a cane.

Dr. Mark Johnson, the Brigham brain surgeon who treated Lambert, believes his patient’s experience is hardly unique. “I think there are a large number of patients out there who are suffering from gait instability, dementia, and incontinence who could be treated effectively if only the proper diagnosis could be made,” said Johnson, an associate neurosurgery professor at Harvard Medical School.

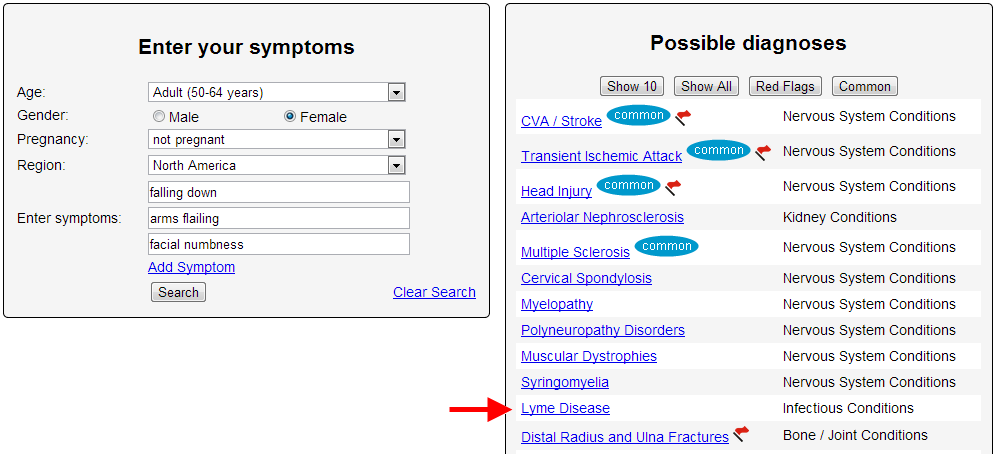

Ann Marie Cosgrove told FOX 9 News she wanted to share her cautionary tale because after years of suffering from Lyme disease, she hit rock bottom back in February. "I was falling over. I was using a cane to walk," she recalled. "My arms were flailing by themselves. My whole face would turn numb, just go numb." As her condition worsened, she felt like doctors were failing her -- unable to properly diagnose the tick-borne illness. "People didn't recognize me. People thought I was dying," Cosgrove said. "I felt like I was dying." The usually-active educational assistant remembers the conversation she had when she was kicked out of an emergency room verbatim. "'Don't come back here. We can't fix you. We don't know what the problem is,'" she recited. For Cosgrove, the biggest issue was that she never got the telltale bulls-eye rash that is the hallmark of Lyme disease, and her tests kept coming back negative.

"The rash is very suggestive, but not everybody gets it," said Dr. Frank Rhame, an infectious disease specialist with Allina. "Maybe 40 percent of people don't get it." Rhame conceded that the disease can be tough to diagnose, but the Minnesota Department of Health reports a dramatic increase in cases since the 1990s. In 2012, there were 912 confirmed cases in the state with another 604 considered probable. Early symptoms include the rash, fatigue, chills, fever, and aching muscles and joints. "If they just feel crummy, and they have been up north, think Lyme," Rhame recommended. After her multi-year ordeal with the disease, Cosgrove is now getting better and hopes others will realize that a tiny pest can become a big issue. "I don't want anyone to go through what I went through," she said. Rhame says cases like Cosgrove's are rare because most people can ward off the bacteria before it wreaks havoc on the body -- even without treatment; however, advocates are concerned about the growing number of misdiagnoses. Doctors have mistaken it for chronic fatigue syndrome, Crohn's disease and even early ALS. Many hope more public awareness will make a difference.

On the final day of the inquest into Sara Hampel's death in October 2011 at Gove Hospital in Nhulunbuy, Northern Territory Coroner Greg Cavanagh said it appeared her severe sepsis should have been identified earlier.

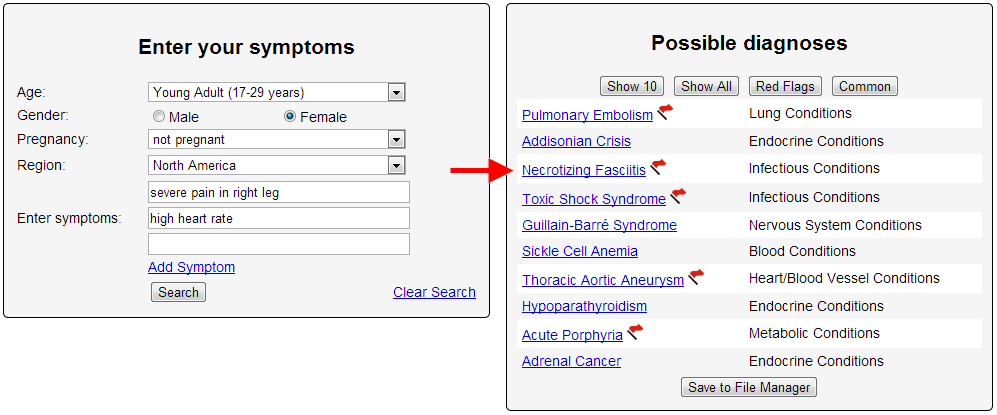

Sara Lorraine Hampel, 21, had given birth to her first child eight days before she was taken to Gove Hospital at Nhulunbuy in the early morning of October 14, 2011, complaining of severe cramp-like pains in her right leg.

The inquiry heard that doctors did not suspect sepsis initially because Mrs Hampel did not have a fever, a key indicator. A pathologist, Professor Robert Baird, told the inquest that under new protocols it would have been identified based on other factors, including her heart rate, platelet count and severe pain.

Northern Territory Coroner Greg Cavanagh heard it took doctors hours to even consider she was suffering from necrotising fasciitis, an infection of the tissue surrounding muscle.

The inquest in Darwin heard the bacteria, which caused severe sepsis in Mrs Hampel, went undiagnosed and untreated with antibiotics until the late afternoon, by which stage she had become critically ill.

Mrs Hampel suffered a cardiac arrest and died on a Careflight plane later that night as she was awaiting transportation to Royal Darwin Hospital, about 600 kilometres to the west.

Mrs Hampel's father Chas Nokes says he hopes the inquest will provide some answers about her death and pleaded for changes to hospital protocols.

"It just sits in everyone's mind how young, healthy and how agile someone can be and then, in 24 hours, can be gone," he said. "You get hit with a bus, you know why.

"It's probably trying to find the reason, what that bus was." The inquest continues.

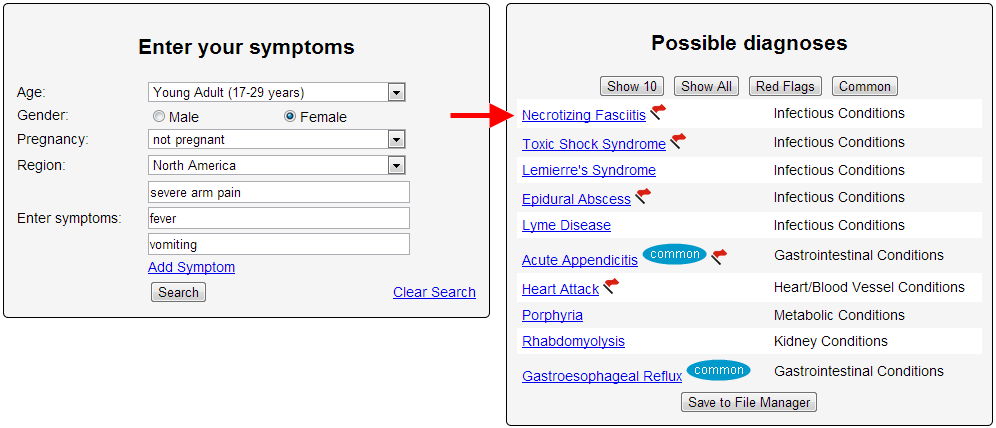

Attorneys for OU have argued that staff at Hudson were not incompetent for not recognizing necrotizing fasciitis. Expert medical witnesses for the defense have said that the infection is a rare condition almost never seen in healthy young people with no predisposing conditions such as diabetes, intravenous drug use or colon cancer. Therefore, they argue, for a physician to miss it in Millsop's case is not surprising. In a memo supporting their latest court filing, however, Millsop's attorneys allege that Hudson's medical personnel simply ignored Millsop's repeated complaints that something was very wrong with her. According to a recounting of alleged facts in the document, Millsop began feeling ill the evening of Sept. 5, 2007, with a fever and shaking. She called her brother in Nelsonville, who drove her to O'Bleness Memorial Hospital. After being seen briefly by a doctor or nurse there, the document states, Millsop's fever dropped, and she decided to go to her brother's home. The next morning, the court filing claims, Millsop experienced a "stabbing pain" in her right arm above her elbow, as well as nausea and chills. She went to Hudson around 8 a.m., at which point "the pain in her arm seemed to be spreading." A physician at Hudson listened to Millsop's symptoms during a 10-minute exam, the document says, and swabbed her throat for a strep infection. When Millsop expressed concern about her arm pain, the filing claims, the physican "did not seem to think the pain was relevant," and asked if Millsop might have injured her arm during exercise. She then diagnosed Millsop with acute pharyngitis and muscle strain. Millsop returned to her dormitory, where her pain got worse and continued to spread, and she suffered alternate fever and chills, her attorneys allege. She returned to Hudson, where she told the physician who had seen her earlier that "she felt like she was about to pass out, and that she couldn't breathe because her arm hurt so badly," according to a deposition. The physician allegedly told her that "if she could get her breathing under control… the pain would lessen." Millsop began vomiting soon afterwards. The physician diagnosed Millsop's suffering as hyperventilation stemming from "an adjustment reaction with anxiety," based on being away from home for the first time – though Millsop had been on a trip to Europe the year before without her parents. Though Millsop repeatedly complained to Hudson staff about her increasing pain, the document alleges, "no one seemed to pay attention," and staffers "seemed to think that Molly just needed to calm down." She called her father, who agreed to come and pick her up.

While he was on the way, she called him again, seeming to him "incoherent" and saying she was in "a great deal of pain." While waiting for her father, the motion alleges, Millsop asked a nurse if she should go to the O'Bleness emergency room, and was told that "the emergency room was not likely to do anything for her that the health center wasn't doing." Millsop's father has testified that when he got to Hudson, he got the impression that staff felt his daughter "was being over-dramatic." He described his experience there as "almost surreal." After he got Millsop to O'Bleness, she "began to scream from the pain in her arm," according to her and her father's depositions. When X-rays were taken of Millsop's arm, an O'Bleness physician concluded she was suffering from necrotizing fasciitis, and would need to be flown immediately to a Columbus hospital. She was rushed into surgery in Columbus, and a nurse told her father that surgeons "were working very hard to save Molly's life," but might have to remove her arm. They ended up having to do so, to prevent the infection spreading to her vital organs, the court filing says. A trial to determine OU's liability is scheduled for April.

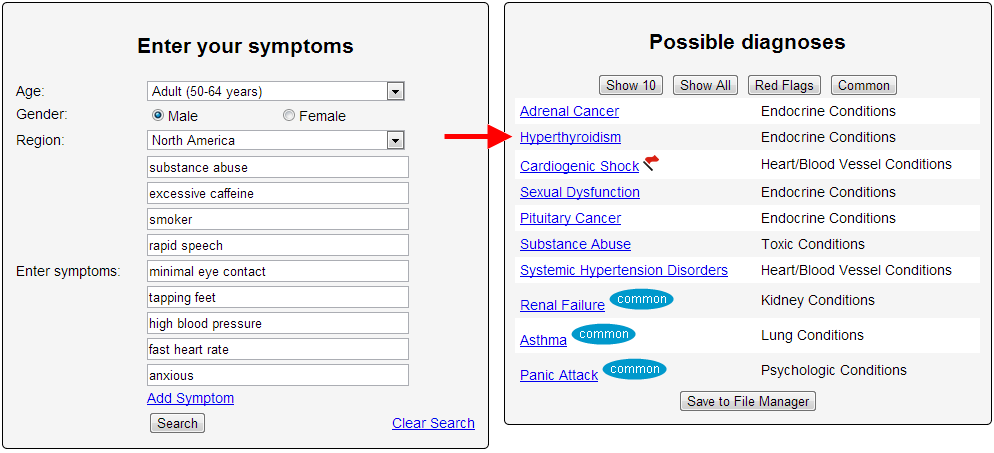

Mr. T, a white man aged 51 years, presented to a free clinic for management of hypertension and to obtain prescriptions. He had a history of homelessness, substance abuse and mental illness. He reported no other comorbidities, family history or past medical issues. He stated that his hypertension was well managed with a two-drug regimen. After several visits, the clinic staff members noted that Mr. T's pulse and BP fluctuated drastically. He was on a beta blocker to manage hypertension, but he also reported consuming at least two pots of coffee per day. Additionally, Mr. T stated that he had increased anxiety when he came to the clinic because there he would see people with whom he had previously used drugs. Mr. T routinely refused laboratory evaluation and would not return for follow-up appointments with any regularity. Given his nonadherence to medication and follow-up, the providers began to question other causes of his tachycardia and hypertension, notably extreme anxiety and possibly substance use.

- History - Mr. T was previously homeless but was working in sales at the time of his appointment. He reported no current use of alcohol or illicit drugs but admitted to smoking one to three packs of cigarettes a day, depending on his anxiety level. Mr. T also reported taking metoprolol (Lopressor, Toprol) 50 mg b.i.d. and hydrochlorothiazide once daily for treatment of hypertension.

- Examination - On presentation, Mr. T appeared anxious. His speech was rapid, he displayed minimal eye contact during consultation, and he tapped his feet throughout the visit. The patient's BP was mildly hypertensive (145/82 mm Hg), and his pulse was 68 beats per minute. Mr. T's BMI was 20.87. Head and neck exam were unremarkable, lung sounds were clear, and heart rhythm was regular without extra sounds. An abdominal exam was also unremarkable with normoactive bowel sounds. No peripheral edema was noted.

- Laboratory Data and Diagnosis - Given Mr. T's history of polysubstance abuse, and his anxiety symptoms, the providers doubted he would return for additional testing. Thus, a battery of tests were ordered, including a lipid panel, hemoglobin A1c, a complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel, and several thyroid tests (triiodothyronine [T3], thyroxine [T4], and thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH]). All labs returned within normal limits except for the thyroid studies. Mr. T's total T3 was 481 ng/dL (normal 80-175 ng/dL), total T4 >30.0 µg/dL (normal 4.9-12 µg/dL), and TSH <0.01 mIU/L (normal 0.3-5.50 mIU/L). Given these results, Mr. T was sent for a thyroid uptake study, which was 59%, well above the normal range of 7% to 30%. Hyperthyroidism, specifically toxic diffuse goiter with mention of thyrotoxic crisis or thyroid storm, was diagnosed.

- Treatment - Endocrinology was consulted, and Mr. T was started on methimazole (Tapazole) daily in addition to his metoprolol. Within a week, the patient noted decreased anxiety, and his BP and pulse began to normalize.

- Discussion - Following recommendations for the care of homeless patients,4 a comprehensive and ongoing history was obtained at each clinic visit. Mr. T's physical exams, while normal, did elicit tachycardia, which he explained was the result of his anxiety and walking to the clinic. His caffeine consumption also explained his tachycardia symptoms, as overconsumption can lead to cardiac side effects. While hyperthyroidism, anxiety and substance abuse should be differential diagnoses when a patient presents with caffeine intoxication,5 Mr. T's refusal of baseline labs and the medical management of his hypertension complicated and delayed his diagnosis for more than one year.

The father of a deceased woman accuses a Maryville and a Staunton hospital of misdiagnosing a medical condition that he says led to his daughter’s death.

John W. Wasielewicz, independent administrator of the estate of Jeanette M. Bailey, filed a lawsuit Nov. 7 in Madison County Circuit Court against Southwestern Illinois Health Facilities Inc., also known as Anderson Hospital, doing business as Express Care. Community Memorial Hospital Association is also named as a defendant.

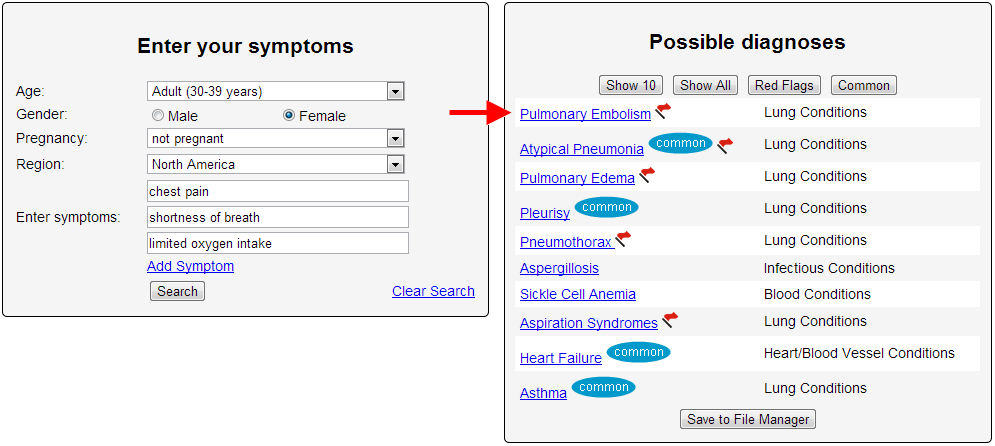

According to the complaint, Bailey went to Anderson Hospital’s Express Care, an urgent care center, in December 2011 complaining of chest pains, shortness of breath and limited oxygen intake. Wasielewicz says Dr. Rebecca M. Hoffman treated his daughter and diagnosed her as having bronchitis.

Wasielewicz claims his daughter’s condition continued to worsen over the next five days and she was admitted to the emergency room at Community Memorial Hospital. There, Bailey was under the care of Dr. Timothy A. Mathison who allegedly diagnosed her as having pneumonia. Bailey was released, according to Wasielewicz, but returned to the emergency room the next day suffering from a heart attack. She was pronounced dead less than 30 minutes later.

Wasielewicz says the autopsy revealed his daughter died of pulmonary thromboembolism, an obstruction of blood flow to the lungs. He alleges both hospitals misdiagnosed Bailey’s illness and failed to perform the proper tests necessary to properly diagnose and treat the ailment.

Anderson Hospital and Community Memorial are being sued for negligence and wrongful death. Wasielewicz asks for more than $200,000 in damages and court costs.

Attorneys David A. Boresi of Hillsboro and David J. Massa of Maryville represent Wasielewicz. They ask for a jury trial.

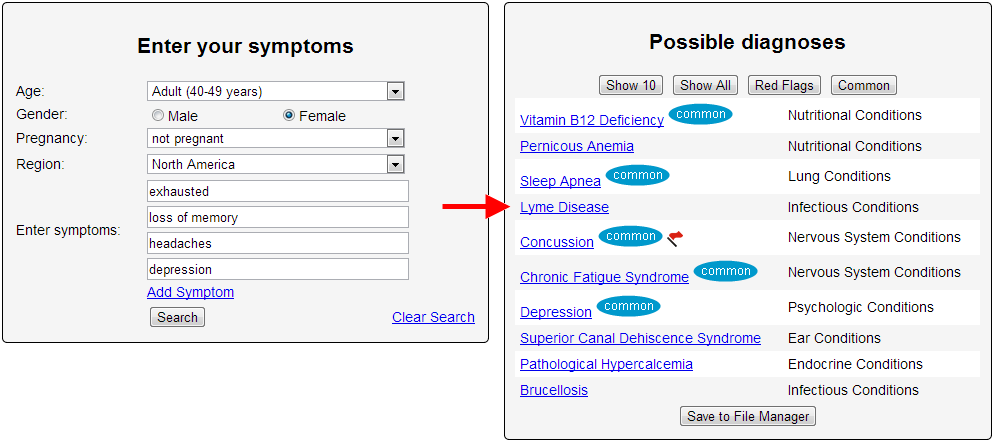

Around two years ago, I started to get sick. No-one was quite sure what it was, and I went from doctor to doctor, in a bid to try and figure out what was wrong. I seemed to have all the symptoms of hypothyroidism, but my TSH levels were normal, and the only other explanations people could come up with was that I was very busy and it wasn’t surprising I was tired, with so many children and so many books to write. Eventually, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome was thrown into the ring. And depression. A psychiatrist told me it was all in my head, and put me on medication that made it much, much worse. The side effect of the medication was instant, and tremendous, weight gain. I lay in bed for most of that year, too exhausted to engage in life, bewildered by my changing body and how it was betraying me, desperately wanting to get my old life back. In March this year, after 15 months of being a zombie, I took myself off the medication, convinced that was the cause, that I would feel like myself again within a few weeks. Nothing changed. Finally I went to Dr. Frank Lipman in New York who discovered that I have no T3 thyroid hormone, and that the medications I had been on had messed me up terribly. So I was right about something. He found my hormones to be completely out of whack; I have something called Estrogen Dominance. Plus various deficiencies of minerals and vitamins. I started taking thyroid medication, but didn’t feel better.

Finally, in desperation, I went to a neurologist to do a full panel of bloodwork, and this is what he has found: I have Lyme Disease. Actually, because I was never treated when I was infected, my Lyme has now turned into Post-Lyme Auto-immune Syndrome, although, I am now being treated for Lyme. And I have Anaplasmosis, another tick-borne disease. I have Hashimoto’s Disease, and a whole host of other, smaller things like Neuropathy, Raynaud’s Syndrome, not to mention the constant exhaustion, depression, memory loss, headaches and weight change.

My friends have watched me retreat over the last two years, from a vivacious, energetic, busy woman who was always juggling, to someone who barely leaves the house, who is in bed every afternoon, who is a shadow of the person she once was. My doctor explained his belief that everyone in this Tri-state area has Lyme. You cannot avoid it, but not everyone will get sick. I have been bitten by many ticks over the years, and getting sick never occurred to me – I was Superwoman. I would never get sick. The one thing I'm certain is that we are not crazy, and it's never in our heads.

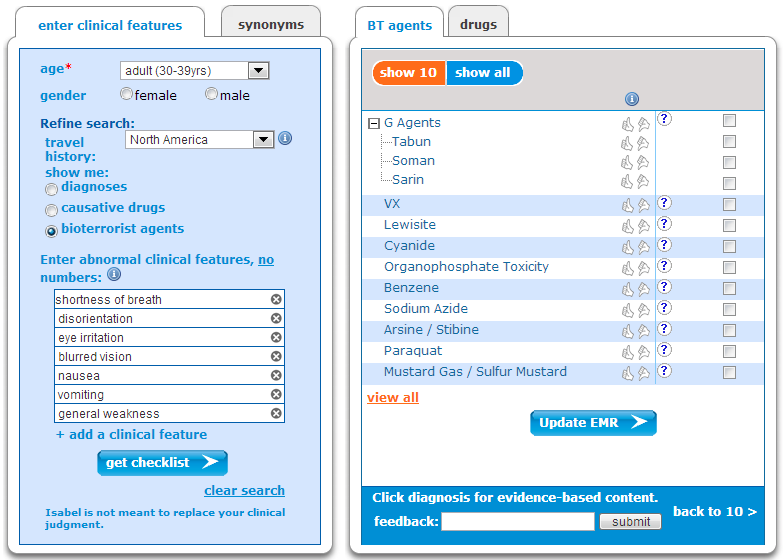

The United Nations team investigating a chemical weapons attack last month in Syria has found that sarin was used. "In particular, the environmental, chemical and medical samples we have collected provide clear and convincing evidence that surface-to-surface rockets containing the nerve agent sarin were used in Ein Tarma, Moadamiyah and Amalaka in the Ghouta area of Damascus," a 38-page report says. Chemical weapons "were used on a relatively large scale," U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said in a briefing to the U.N. Security Council. It's "the most significant confirmed use of chemical weapons against civilians since Saddam Hussein used them in Halabja in 1988," Ban said. The U.N. mission "adhered to the most stringent protocols available for such an investigation, including to ensure the chain of custody for all samples," Ban added. The team interviewed survivors and first responders, and collected hair, urine and blood samples. "The Mission also documented and sampled impact sites and munitions, and collected 30 soil and environmental samples -- far more than any previous such United Nations investigation," Ban said. The report presents a stark picture of the horrific events of August 21. "Survivors reported that following an attack with shelling, they quickly experienced a range of symptoms, including shortness of breath, disorientation, eye irritation, blurred vision, nausea, vomiting and general weakness," Ban said. "Many eventually lost consciousness. First responders described seeing a large number of individuals lying on the ground, many of them dead or unconscious." The weather made things worse. Falling temperatures at the time of the attack meant the downward movement of air, allowing the gas "to easily penetrate the basements and lower levels of buildings and other structures where many people were seeking shelter," Ban said. The U.N. mission has not completed its investigation of other alleged uses of chemical weapons in Syria, Ban said.

(Drugs not available on Symptom Checker)

But there's no doubt chemical weapons were used in the attack last month, he said. "The United Nations Mission has now confirmed, unequivocally and objectively, that chemical weapons have been used in Syria." "This is a war crime and a grave violation of the 1925 Protocol and other rules of customary international law. I trust all can join me in condemning this despicable crime. The international community has a responsibility to hold the perpetrators accountable and to ensure that chemical weapons never re-emerge as an instrument of warfare." The U.N. mission's mandate, however, did not include assigning blame for the attack. It's unclear how the U.N. report may affect international dynamics of the Syrian conflict. The United States and Russia reached an agreement over the weekend aimed at averting U.S. military action against the Syrian regime. President Obama, on Monday, called that "an important step." "We're not there yet. But if properly implemented, this agreement could end the threat these weapons pose not only to the Syrian people, but to the world," he said.

Full Case Discussion - CNN

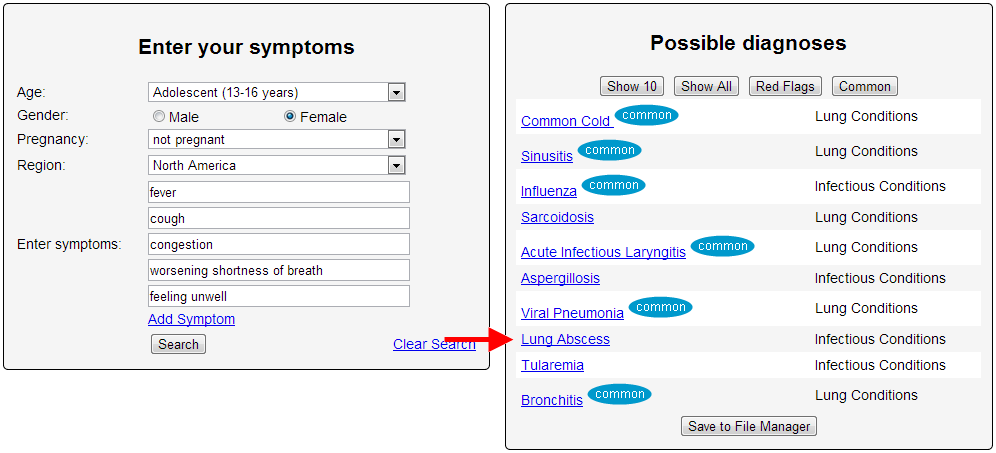

The stethoscope certainly has limitations! Just 2 days back, I saw an adolescent girl in our ED with a 10 day history of fever, cough and congestion, and worsening shortness of breath for 1-2 days; she was diagnosed with atypical pneumonia (aided by xray chest) at the onset and treated with zithromax; when she did not improve, she was started on amoxycillin on day 5 for probable sinusitis.

When I saw her, she was looking unwell, though her vital signs were not remarkable; had a SaO2 of 97%; in no objective respiratory distress, and her auscultatory exam was normal.

But based on her history, and in spite of non-contributory exam, I was concerned enough about the possibility of worsening pneumonia that I repeated a chest xray which showed a big opacity in the rt upper lung field with an air-fluid level, suggestive of a lung abscess (confirmed on US later).

The stethoscope here did not help, but I don't think that the answer is to throw it away, rather to understand its limitations, and use all the diagnostic clues available.

The reason is that in so many other situations, the stethoscope does aid in making a diagnosis. For example, every day on a shift, I see a child with mild shortness of breath, no audible wheeze, but where using a stetho., one can hear bilateral symmetrical wheeze; using the same instrument, one can confirm normal heart sounds without a gallop or murmur, and no hepatomegaly on abdominal palpation (thus making CHF unlikely), and I have a diagnosis of an asthma flare, and > 99% of the time that is what it is, and everybody is happy!

Sure, if a better version of the stethoscope comes, then we shall all go buy it. Who would buy the original IPhone today when 5S is available?

A Hayward emergency room doctor has had a reprimand added to her Minnesota license because of an action taken in Wisconsin.

Dr. Dorothy A. Novak, 63, was reprimanded by the Wisconsin Medical Examining Board on March 20 because of an incident on April 8, 2012.

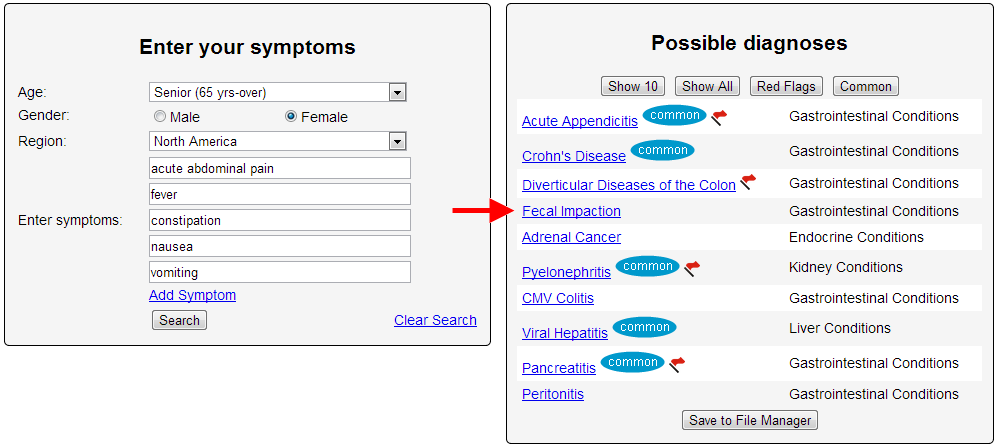

According to the Wisconsin board’s findings: An 86-year-old woman came to the ER that day complaining of three days of abdominal pain with constipation, fever, nausea and vomiting.

Novak ordered an enema, which failed to produce significant results. Novak sent the patient home with instructions to drink four quarts of an electrolyte solution to empty the colon, and then to continue using the solution daily.

The patient returned to the ER about 11 hours later complaining of incapacitating abdominal pain. After examination by another doctor, she was flown to another hospital, where she was found to have a large inflammatory mass in her pelvis. She died the next day.

The board ruled that Novak should have diagnosed an obstruction, and that the patient should have been hospitalized for observation. Novak was required to take a continuing education course on acute abdomen presentation and treatment and to pay $350 in costs. She did that, and her license was fully restored on May 10.

The Minnesota reprimand occurred on Sept. 7. In an interview, Novak said it reflected the action taken in Wisconsin. She said that at one time she practiced in Duluth emergency rooms, but she hasn’t done so for at least 10 years and doesn’t plan to.

Nonetheless, she keeps her Minnesota license active, and the reprimand appeared when she reapplied this year, she said.

Novak was reprimanded once previously, in 2008, when the Wisconsin board ruled she had failed to diagnose testicular torsion in a patient in a 1999 incident. In that case, she was fined $400.

Novak said she didn’t hire a lawyer to represent her in either case but might have had it been earlier in her career. She thought the board overreached, she said.

“The medical boards are under a lot of pressure from the media,” Novak said. Of the 2012 incident, she said, “I don’t think I misdiagnosed the patient. I don’t think I was entirely responsible.”

Novak, who also is licensed as a family physician, continues to practice in the emergency room in Hayward and says she has no plans to retire.

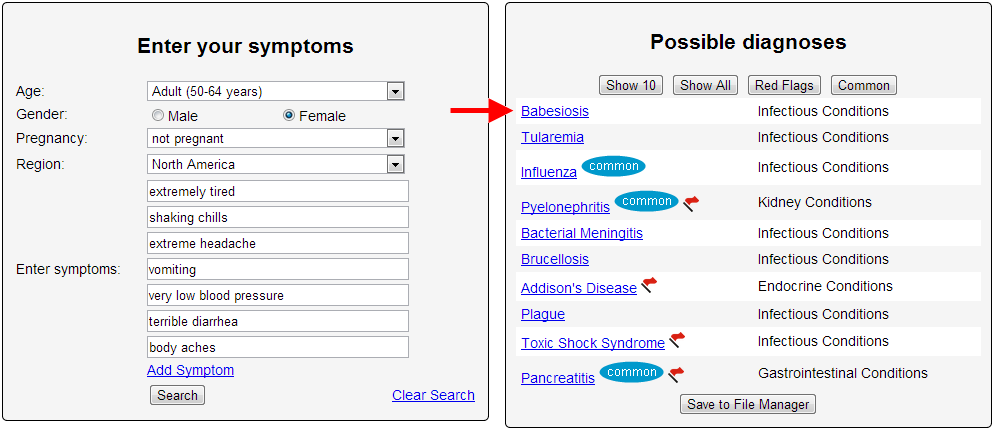

Now the 59-year-old woman lay on the floor. She was completely still except for her right hand, which jerked and shook. Her eyes rolled back in her head. By the time the ambulance arrived, her blood pressure was dangerously low, and her heart was racing. She was rushed to Waterbury Hospital in Connecticut. The woman lay on the stretcher, still dressed in her street clothes. The doctor took in all the immediately available data: her face, tanned but strangely pale; the rapid beeps of the monitor, clocking her heart’s accelerated rate; her low blood pressure. She was more tired than she’d ever been in her life. When she first got sick, she had an awful headache; she had been vomiting and had terrible diarrhea. There was a heat wave in central Connecticut, but she was shivering from some inner chill. The next day, she wasn’t vomiting, and the diarrhea was gone — but her head still ached, and she still felt tired. She thought she might have the flu. Finally her husband called her doctor. When the doctor heard that his normally active patient had spent more than a week on her couch, he suggested she go to a nearby urgent-care center and get checked out. But she didn’t want to go. Her headache was gone, and her muscles didn’t ache quite so much. She was able to get through more of the day before the fatigue forced her back onto the sofa. But then, just a couple of hours earlier — wham — it was as if a knife had been thrust into her belly. She vomited. The patient didn’t smoke or drink. Her cholesterol was a little high, she told Robey, but she was otherwise healthy. She didn’t recall any recent tick bites. Although Robey could tell she was sick, it was hard to locate the problem. Her lungs sounded clear. She had a little tenderness just below the ribs, but it wasn’t impressive. It was her blood pressure, measuring in the 70s and 80s, that worried the doctor most. He started her on IV fluids, but he still couldn’t say why her blood pressure was so low. She had been vomiting, and the loss of fluids could bring blood pressure down. Was that enough to make her this hypotensive? Why would an apparently resolving infection suddenly worsen? Robey ordered a chest X-ray and blood tests to look for signs of infection, then waited for the fluids to do their work. The results of the tests came in over the next hour. Her chest X-ray was normal. Her liver and kidneys showed signs of mild injury, and she was slightly anemic, but none of this seemed very likely to make the woman this sick.

Robey took a call from the lab technician, who said he would need to order additional testing but that it looked as if this woman had something inside her red blood cells. Could she have a disease called babesiosis? That made sense to Robey. The patient was a passionate gardener — in the Northeast, in the summertime — with something visible inside the red blood cells. Babesia are increasingly common parasites spread by the same deer tick that carries Lyme disease. After an infected tick bites, the tiny organisms penetrate the red blood cells and begin to replicate. The red blood cells, filled with parasite offspring, split open, releasing the brood into the circulation, where they can continue their cycle of penetration, reproduction and destruction. Robey immediately ordered the necessary tests and started the woman on intravenous antibiotics. But he was uneasy. Most people with babesiosis have no symptoms at all or get an illness so mild that they don’t even go to the doctor. The usual symptoms, when present at all, include fatigue, fever, headache and nausea — the same ones this woman described. Her blood pressure remained dangerously low, even though she had received three liters of fluids. And she still felt awful. Suddenly she stopped talking. Her eyes rolled up, and her right arm began to twitch and shake. The episode lasted only a few seconds. It looked to Robey as if she had fainted. There was clearly something more going on than garden-variety babesiosis. Blood loss could make blood pressure dangerously low. Was she bleeding inside somewhere? There have been reports of babesiosis causing the spleen to rupture. But he thought it was more likely she had something completely unrelated to the babesiosis. Was this some other infection — an abscess somewhere? Robey decided to get a CT scan to look in her abdomen — if she was bleeding, that was the most likely spot — if that didn’t reveal anything, he’d do a spinal tap to look for something in the brain.

And the winner is: After this case was posted on Aug. 1, more than 300 answers were submitted; only five correctly diagnosed it. Patricia York of Ellicott City, MD., a nurse, was the first. She remembered that babesiosis could cause the spleen to rupture.

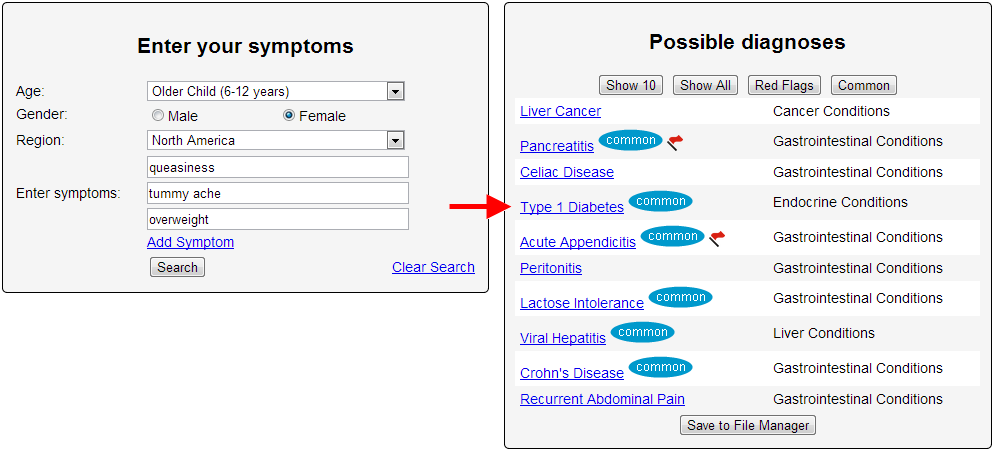

The little girl could barely breathe. She lay on the hospital bed, her chest rising with each forced inhalation. Irma Nicanor held her only child's hand. The six-year-old's eyes were closed, but Irma felt her tiny fingers squeezing.

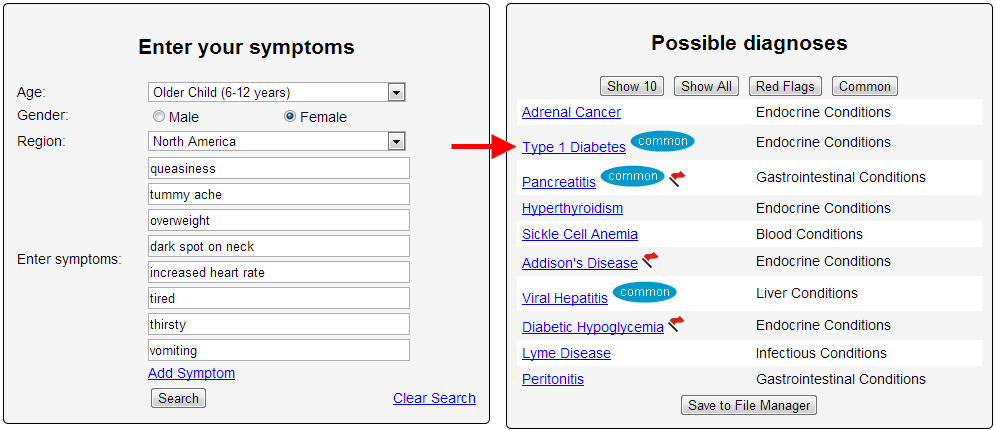

Irma was dazed by how everything had gone so bad so quickly. It was early on a January evening in 2010. They'd checked into New York Hospital in Flushing that afternoon. Claudialee was nauseated and had a tummy ache. Irma figured she'd caught a stomach virus from a boy in their apartment building. She now knew that it was more than that. Two days before, Cladialee was running around the house, climbing over couches and crawling under tables. She seemed as healthy as she'd ever been. Yes, she was overweight, and her blood sugar was slightly high, but Irma was seeing to it that her daughter would get fit.

A bubbly girl with a loud laugh, full cheeks, and a thick mop of dark brown hair, Claudialee had plenty of energy for that mission. The girl took ballet and karate lessons. She ran around the park with her dad and rode bikes with her cousin. During snack time at P.S. 32, she pulled out sandwich bags filled with celery and carrots and sliced fruit. Her first-grade teacher would eat with Claudialee so that she wouldn't feel bad about not having sweets like the other kids.

Irma was always conscious about her daughter's health. Over the past three months alone, she'd taken Claudialee to six medical appointments: three times to her pediatrician, Dr. Thelma Cabatic, for flu shots and checkups; and three times to her endocrinologist, Dr. Arlene Mercado, to deal with her blood sugar. At each visit, Mercado would tell Irma that her girl was fine, in need of nothing more than diet and exercise.

Yet two weeks after her last checkup, here was Claudialee struggling for air, half-conscious in an emergency room. "Patient has slight movement of all four extremities spontaneously but not on command," the hospital notes read. "Mumbles occasionally."

The scene was overwhelming for a mother. Nurses scurrying around. Chemicals with smells much stronger than the cleaning supplies Irma used in her job as a housekeeper. Intravenous tubes attached to Claudialee's arms, alternately streaming potassium salts, water, and glucose. The girl's blood sugar had risen to 525 milligrams per deciliter—more than five times the normal level.

How could this happen? Irma kept asking herself.

Claudialee's lungs struggled as the night wore on. Nurses strapped an oxygen mask to her face. It wasn't enough. They decided to push a tube down the child's throat so a ventilator could help her breathe. But Claudialee wasn't having it. Even half-conscious, she was still a flare of vigor. Her arms flailed and her legs kicked. The nurses didn't expect such strength. They retreated and injected her with a sedative. Then they inserted the tube. Claudialee was now unconscious and dependent on a machine to supply her with oxygen.

Irma sat in the waiting room, praying. She called her sister Marta. It was about 4 a.m., but Marta rushed to the hospital. She got lost in the hallways, missed the waiting room, and ended up at Claudialee's bedside. The two were alone, the only sounds coming from the robotic hums and beeps of intensive care.

"It hurts," Marta thought she heard the girl whisper.

"Where does it hurt?"

There came no reply.

St. James Avenue was quiet and still on October 31, 2009. Irma and Claudialee passed the modest wood-frame homes with yards fronted by low chain-link or wrought-iron fences. Just the kind of tranquility a family hopes for when they move to Elmhurst.

Mother and daughter stopped in front of a cream-colored three-story house, then walked up the driveway to a concrete backyard. Irma might as well have been taking Claudialee to a classmate's birthday party.

Court documents, medical records, and interviews would detail what followed.

The pair descended a stairwell to a minimalist setup: a desk and several chairs. Curtains forming two makeshift rooms. Dr. Arlene Mercado's office was in the basement of her sister Myra Mercado Capistrano's house.

Mercado opened the clinic in 2007. Thirteen different insurance companies listed her practice in their network. She had a second practice at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn. And she accepted Medicaid, the government health program for low-income people. She was a pediatric endocrinologist, specializing in children and the hormones and chemicals that could stunt growth or bring on early puberty. The most common issue she dealt with was diabetes.

She was well versed in practice, if not theory. Mercado was not board-certified in her specialty, American Board of Pediatrics records show. She failed the certification exam more than five times. Without passing that, she couldn't attempt the next step, the pediatric endocrinology test. But these setbacks didn't stop her. Board certification isn't mandatory. In fact, though she couldn't pass the test herself, Mercado taught a certification-exam review course in Children's Hospital at SUNY Downstate.

Irma handed William a referral card from Claudialee's pediatrician, Dr. Cabatic.

She'd taken Claudialee to see Cabatic five days earlier for the first in a series of flu vaccinations. Claudialee had the sniffles, so Cabatic ran her through a full examination. Four days later, the doctor called to say that Claudialee's urine and red blood cells showed abnormal glucose levels. Her blood sugar was above normal, suggesting the girl might become diabetic. In her notes, Cabatic wrote, "probable diabetes mellitus."

The disease stems directly from high blood sugar. In type 1 diabetes, the immune system kills off cells that produce insulin, the hormone that brings the body's glucose supply to muscle and fat. If the body doesn't get more insulin, the person will die.

In type 2, a person has a lot of insulin, but the stuff just doesn't work. Insulin resistance, doctors call it. Obesity is the usual cause. The damage is slower and can be treated through diet, exercise, and medication.

Cabatic knew Claudialee was at high risk for diabetes. The girl's maternal grandmother, paternal grandfather, and three of her uncles had it. She recommended that the girl see a specialist and gave Irma the name of a pediatric endocrinologist who spoke Spanish and would accept her Metroplus Medicaid card.

After asking about the family history, Mercado took a blood sample from Claudialee. She told Irma she would send the blood to a lab and they'd discuss the results in two weeks.

The test would duplicate Cabatic's results: Claudialee's blood sugar level was higher than normal, but not high enough to be considered diabetes. She was "prediabetic." During the next visit, Mercado explained to Irma that the results were nothing to be too concerned about. The girl just needed to lose weight. Diet and exercise. She handed Irma a sheet of paper with a food pyramid on it.

In her notes, Mercado wrote that if the patient didn't lose weight by her next checkup in mid-December, she would prescribe Metformin, a drug used to treat type 2 diabetes.

Though type 2 used to be called "adult-onset" diabetes, Mercado knew recent studies had shown that a growing number of kids were getting it. At 3-foot-9 and 67 pounds, Claudialee was clinically obese. Mercado noticed a dark spot on her neck, often a sign of insulin resistance.

By her next appointment on December 12, things were looking up. Claudialee was thinner. Mercado didn't conduct any tests or ask many questions. It was a brief but reassuring meeting, full of grins and calming words. Claudialee is fine, the doctor told Irma. She just needs to drop another pound or two. Diet and exercise.

In her notes, Mercado wrote that she'd administer another blood glucose test on the next visit. As Irma left, William handed her an appointment card telling them to come back on February 23.

Cabatic echoed Mercado's optimism when the mother and daughter returned on January 9 for the girl's final flu shot. It happened that Claudialee had come home early from school the day before. During snack time, she complained that her heart was beating faster than normal. The nurse sent Irma a note saying a doctor had to sign off before Claudialee could return to class. Cabatic assessed her vital signs. Normal heart rate and blood pressure. No cough. No chest pain. No difficulty breathing. All was stable.

Cabatic had more good news: In the 10 weeks since the October 26 checkup, Claudialee had lost five pounds and grown two inches. As far as the doctors could tell, Claudialee was getting healthier by the week.

On January 21, Marta Nicanor, Irma's sister, picked up her six-year-old son, Gustavo, and Claudialee from school. Irma worked as a housekeeper for a family in Port Washington,Long Island. Claudialee told Marta she was tired and that her stomach had been bothering her. She wanted to lie down. Marta called Irma, who called Dr. Cabatic to schedule an appointment for first thing the following morning. She left work early and arrived at her sister's apartment about 4:30 p.m.

Irma took Claudialee's temperature. No fever. She offered food but the girl wasn't hungry. She was very thirsty, though. Irma placed Gatorade and ginger ale on the nightstand by her bed, but Claudialee only wanted water. She napped for a couple of hours, then gulped more water. She fell back to sleep at about 10 p.m., with her mother lying beside her.

Claudialee woke up drowsy. She always dressed herself, but on this day Irma had to do it for her.

They made the 10-minute walk and got to Dr. Cabatic's clinic at 9:30 a.m. It didn't open until 10, but Irma routinely arrived at doctors' appointments early. Then 9:30 became 10:30 and 10:30 became 11. The door remained locked. Irma called Cabatic's cell phone and office line seven times. No answer.

Claudialee kept saying her stomach ached, that she felt tired and really thirsty. She'd vomited three more times that morning.

She normally didn't complain about things—she was the type of girl who fell off a scooter, scraped her knee, and got right back on without hesitation. Irma called a cab and asked the driver to take them to New York Hospital.

Claudialee began to sway and stumble as they walked toward the emergency room. Before reaching the entrance, she nearly collapsed. Irma picked her up and carried her the rest of the way.

As hospital workers ran tests, a nurse asked Irma if Claudialee had been urinating more and drinking more than usual recently. Irma said she had noticed her daughter doing both since Christmas.

This suggested that Claudialee's blood sugar had been rising.

The test results—five times the normal level—supported that hypothesis.

"When the doctors came in and told me about blood-sugar levels—that was a surprise," Irma tells the Voice. "That was the last thing I expected to hear. That's when I knew something was really wrong."

There had been other signs. Months after Claudialee checked into New York Hospital's ER, pediatric endocrinologist Craig Alter reviewed her medical records. He was shocked, unable to understand why Dr. Mercado had so quickly ruled out type 1 diabetes.

"If you tell me there is a five-year-old with diabetes, the chance that they have type 1 is probably 99.99 percent," he would later testify. "If you tell me they are obese, I would say, okay, the chance is 99.7. It's almost definitely type 1."

Alter, a physician at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, is one of the world's top experts on diabetes in kids. He teaches a pediatric endocrinology class at the University of Pennsylvania's medical school. He is chairman of the Educational Committee for the Endocrine Society and gives lectures across the globe. In 2001, he founded Camp Freedom, a summer program in Pennsylvania that brings together diabetic youth for a week of swimming, hiking, and sharing insulin-injection stories around the bonfire. Last year, 140 kids registered; 139 of them had type 1.

Even though rates of type 2 are rising among minors, the condition remains rare in children under 10 years old. The National Institutes of Health report that one out of every 5,000 kids in that age group has type 1 diabetes, while one out of every 250,000 gets type 2. The reason is simple: Type 1 is a condition people are born with or acquire very early in life; type 2 develops over time—enough time for the body to build a resistance to insulin.

Not only is type 1 far more common in six-year-olds, it is also far more urgent.

"Type 2, you have a little more luxury of time. Type 1, you do not have the luxury of time," Alter testified. "Type 1, if we don't give them insulin, they will die."

Blood sugar is like temperature—it rises gradually. In the months since Claudialee's last tests, the girl's blood sugar level continued to rise, right under her doctors' noses.

Even as the puzzle pieces began to emerge, each showing a symptom of the disease, neither Mercado nor Cabatic saw the whole picture. Weight loss can indicate that the body is starving as a result of its failure to absorb glucose. Sudden heart palpitations can indicate that the body is dehydrated from losing the sugar-laden fluids via urination.